Reblogged from the Judgement Page of the Oxford Medieval Mystery Cycle site hosted by St Edmund Hall.

In the beginning, there was Drama Cuppers. Not one member of the final cast of Teddy Hall’s 2018 entry in the freshers-only drama competition expected to be part of it, and the cast was only settled, and rehearsals only began, about a week before the first performance. To universal amazement, we not only pulled off our abridged and chaotic production of The Brothers Grimm Spectaculathon, but made it through to the finals, after which we were nominated for several awards. Having been warned that Teddy Hall was not well known for its pursuit of the dramatic arts, we were giddy with our own success. Yet even with these strange beginnings, we could never have predicted what it would get us into.

Later that Michaelmas, Professor Lähnemann, having heard about our Drama Cuppers exploits, approached director Emma Hawkins (2018, Fine Art) about her plan to host a Medieval Mystery Play Cycle, asking if she would be interested in organising a group from Teddy Hall. Based on the popular form of entertainment across Europe in the Middle Ages, the plays were to narrate the greatest hits of the Bible, from the Creation to the Last Judgement, and to be staged at various locations around the college. Emma took the news back to us — and we laughed at her. Us, whose only theatrical experience in Oxford had been an absurd fairy-tale play in which a feminist Snow White rejects her housewife role and retells her own story (having one of the dwarves play her part in drag) — us perform a serious play? About the Bible?

Well, naturally, we accepted the offer. We’d been told we could adapt the script we had been given, which was a modernised version of the Last Judgement from the Towneley Plays. That, we decided — or, rather, hoped — gave us the freedom we would need to pull off something like this. And yet, of course, while we wanted to have fun with it, we were also very conscious that the last thing we wanted to do was to offend anyone in our audience, which was to have an unusually high concentration of vicars. We chose the Last Judgement on the grounds that Revelation — as commentators have noted for more than a millennium — already has some… interesting material. However, we did not think about the other implication of performing the Apocalypse, which is, of course, that nothing comes afterwards. We’d agreed to do the Big Finale, the Last Word on the Matter, the One to End it All, Literally: so it was going to have to be good.

Fortunately, we were gifted with a fascination for theology (both having survived A Levels in Religious Studies with Christianity), a love for Monty Python, and, at least in Alex’s case, a well-oiled understanding of poetic metre (and in Amy’s, a willingness to learn, but some confusion about why it mattered or even what it was). The first round of edits on the original script were made by Emma’s friend, Benedict Mulcare; then we took over, spending eighth week of Hilary repeatedly staying up until the ungodly hours composing and versifying, intoning Miltonic speeches and satirising Brexit — despite Amy’s Law Mods being the following week. As we moved towards the Easter vac, we dragged in as many of our friends as we could cajole, bribe, or blackmail, kicking and screaming, into our cast. We managed to do most of our casting before the vacation, and thought things were well settled. Except for the fact that we hadn’t actually finished the script yet.

We kept on working, though, including making some further revisions to the script whilst on holiday in Germany (never let it be said that we don’t take our Bible seriously) and, although this might not have been entirely conducive to our cast’s learning their lines, things seemed to be going well. Then, in the week before the production, we lost our Jesus (the sort of sentence that by then felt quite normal). Fortunately we found a new one just in time (Joe Rattue, Somerville), who managed to learn his lines within seventy-two hours: which can only be described as a Godsend. This last-minute change was not as difficult as it might otherwise have been, largely because we had done perhaps one rehearsal up until this point — our original readthrough for the purpose of casting — and so Joe really hadn’t missed much.

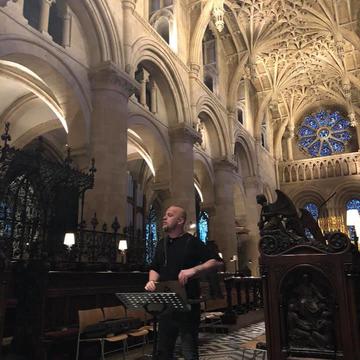

Suddenly, it was Saturday of noughth week, Trinity Term 2019, and we were outside the Norman church that is the St Edmund Hall library, hearing someone in a cassock preface our play in Middle English: a bit of a contrast to what came next. Yet, to our amazement (a feeling we were beginning to grow accustomed to), there was laughter — rather a lot of laughter. And then there was clapping — rather a lot of clapping. Amongst it all there was some puzzlement, but, well, the Word of God has long been subject to that. We had turned the Last Judgement into a satirical comedy, we were the finale to some very poignant and very learned plays, and we seemed to have managed it without offending anyone. One might even have called the resulting applause rapturous. (Sorry.)

Jump forward now past Prelims and the Long Vac: it is Michaelmas Term 2019, the wine has been flowing in true Oxford fashion, and directing, producing, casting, budgeting, marketing, costuming, and starring in (in various combinations) a full-length production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest in a single term feels like a splendid and utterly foolproof idea. Several weeks deep into the all-consuming chaos that followed, Professor Lähnemann approached us again, bringing news of a Second Coming of the Medieval Mystery Cycle, and asking if, after the success of the previous year, we would like to revive the Last Judgement in an expanded version. Again, as though we didn’t already have enough on our plates, we jumped at the chance (this time laughing not with derision but with glee), and, as soon as Earnest was over (with reviews and everything!), set to work on a heavy rewrite of our old script.

Now we had the time, there was a lot we wanted to do. For all our comic intentions, we had some serious messages we wanted to get across. Our first task was to thoroughly expunge, or at least address in a constructive manner, some of the (quite literally) Medieval attitudes that still lingered from the original script. We were alarmed to discover, for example, that Tutivillus, our suave arch-villain, was historically a precursor of racist blackface figures.[1] Secondly, we had tried in our first adaptation to satirise the misogyny of the original: by having the demons treat feminists as comparable to murderers and violent criminals, we hoped to demonstrate the absurdity of the antiquated attitudes found throughout the piece. However, having already had the same demons condemn Donald Trump and co., we realised that then having them criticise feminists made our satire confusingly inconsistent: we wanted sympathy for the devils as they tore apart the Republicans, but not when they did the same to the feminists, so one of them would have to go. This feminist point also hinged perilously on an explanation from Jesus at the end of the play, which, with such limited rehearsals, was in grave danger of being accidentally missed out in performance — as, indeed, it ultimately was.

So, how to resolve these issues? Well, Tutivillus was going to be replaced by Satan, who, to take a leaf out of the seventeenth century’s book, was to be a satire on the Brexiteers. (Alex, writing Satan’s soliloquy, spent far too long finding parallels between Leave Campaign slogans and the fall of Lucifer.) Deeming our feminist efforts sadly unsalvageable, we scrapped the misogyny altogether.

The other thing we fancied was a frame narrative: partly because we thought it would give us a chance to look at Revelation as a text with a complex history, written in uncertain circumstances by an uncertain ‘John’, its canonical status fought over for millennia, its eschatological implications long scrutinised. But mostly because we thought it would be funny.

After going through many possibilities (an early Church synod debating which books were suitable for inclusion in the canon, like they were reviewing X Factor auditions, was a front-runner), we settled on St John himself in the act of writing his Apocalypse. The play, then, was to open with the Angel imparting the Revelation to John, who would bumblingly commentate on the proceedings, interrupting at crucial moments to get an explanation of, say, how the simple breaking of seals could produce such catastrophic events, and how Christ could also be his own Father (except not really). Two years in sixth form of learning all the possible Trinitarian heresies were about to come in handy as we made John utterly fail, over and over again, to toe the line of orthodoxy.

That background theological knowledge could also be troublesome, however. As we read the original play, it occurred to us that the Jesus of the Book of Revelation is, to put it mildly, somewhat different to the Jesus we encounter in the Gospels (at least the gentler ones). The Jesus of the future seemed to place far more emphasis on vengeance and retribution than the great exponent of forgiveness described elsewhere in the Bible. In writing our version, we wanted to explore this problem. We were intrigued by the idea that the story of Jesus has, in large part, been shaped by centuries of translation, reinterpretation, and political and social change, and that his true character may have been lost somewhere along the way. In the 2019 version, we wrote a closing speech in which our Jesus explained that although his role in Revelation would be a deviation from his previous character, his hands were tied by the story set down by John: he was the product of thousands of conflicting beliefs.

In our second version, however, we took an alternative approach. Our frame narrative would allow us to address the reasons for Jesus’ drastically different presentation in Revelation. That said, we thought it might seem a little presumptuous to suggest that a short comedic play written by two students could so easily succeed where aeons of scholarship have failed, and so we opted for farce over realism. Rather than trying to answer the unanswerable question of how exactly millennia of reinterpretation and (mis)translation shaped the Book of Revelation we know today, we simply wanted to ask the question of others, who had Theology degrees and might do the legwork for us.

Once again, we worked through several variations of this story. Initially, we were quite fond of the idea that John was simply illiterate, and didn’t have a very good memory either, but eventually we decided on him not just having any ink. Ultimately, though, our point remained the same — although we had already reworked Jesus’s closing speech from last year’s, we were still keen to further challenge literalist notions of Revelation in a more direct, or at least more slapstick fashion, facetiously suggesting that the whole thing is the half-remembered notes of a man without a pen.

The second script, in all its twenty-five-page glory, was finally finished by the third week of Hilary term. We found a wonderful cast, including our third Jesus; we ordered the most ludicrous array of props, including four rubber horse masks (white, red, black, and pale), which are now decorating our houses; we rehearsed until the end of term, and all in all, we were ready to put on quite the show.

And then the real Apocalypse decided to upstage us.

We still hope that the second version of our play will one day get to be performed, perhaps at next year’s Mystery Cycle. But there’s no need to wait until then. ThE 2020 Judgement play script is available to read in all its sparkling glory on the Judgement page of the Medieval Mystery Cycle website hosted by St Edmund Hall. For the complete experience, you can also read the 2019 Judgement play script, see photographs of the performance – and watch the complete 2019 Judgement drama unfolding!

***

Alex Gunn and Amy Hemsworth are second-year students at St Edmund Hall, Alex reading English and Amy Law and German Law)