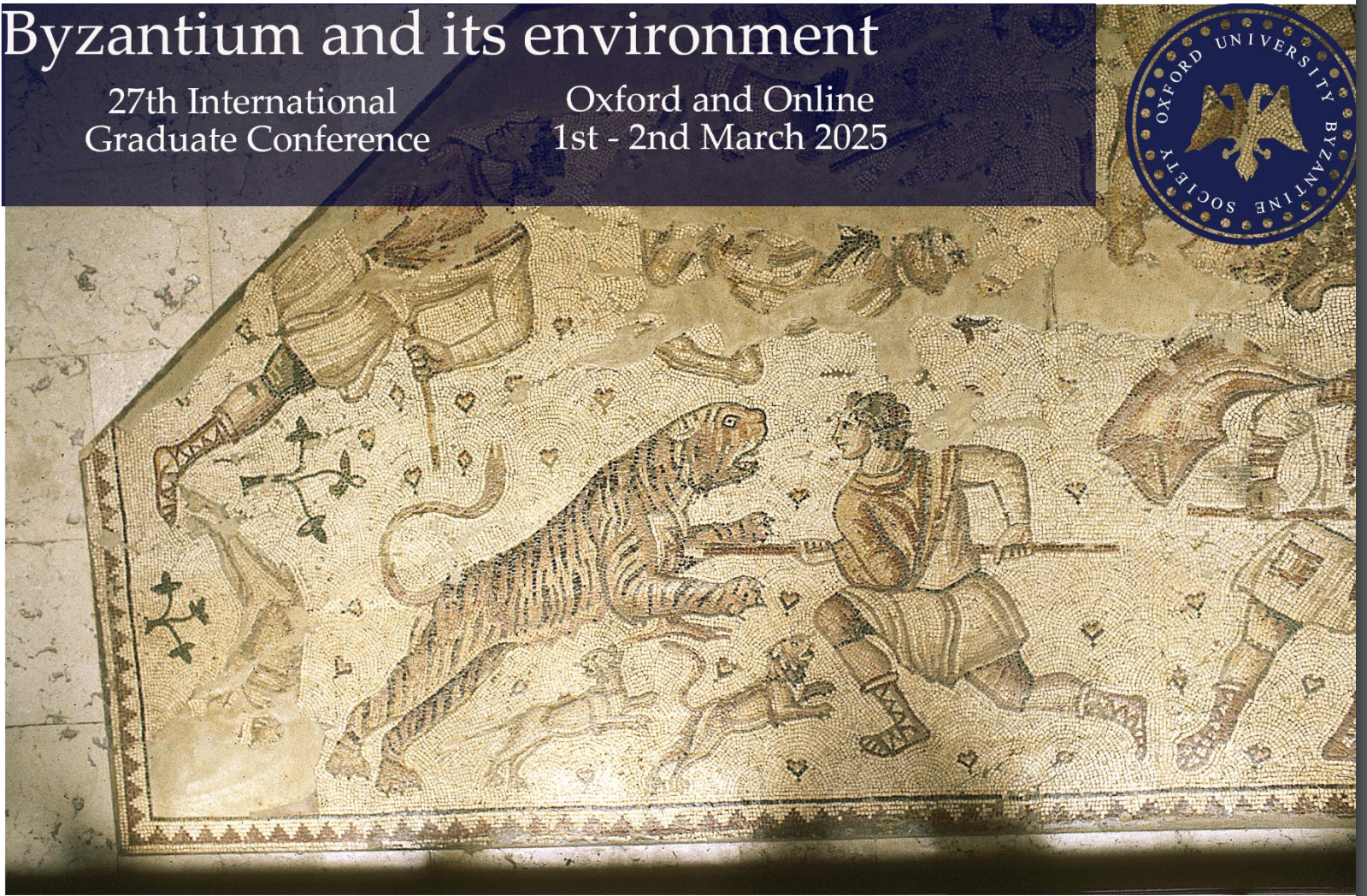

We are delighted to announce the finalised programme (and opening of advance registration for online attendance) for the Oxford University Byzantine Society’s 27th Annual International Graduate Conference entitled ‘Byzantium and its environment’, taking place on the 1st-2nd March, 2025, at the Faculty of History, George Street, OX1 2BE. The programme and abstracts of papers can be found on our website here. The costs for attendance are as follows:

In person attendance: £15 for OUBS members / £20 for non-members

Online attendance: £5

Papers will be delivered in-person, with the proceedings broadcast on a Zoom link which will circulate via email to those purchasing online attendance tickets via Eventbrite. Advance registration for in person attendance is not necessary. If you plan on attending online, please purchase a ticket via Eventbrite here.

We are grateful for the generous support of The Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research (OCBR), The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, and The Faculty of History of the University of Oxford, as well as the many others who have helped with the conference’s facilitation.

We look forward to welcoming you to Oxford. Best wishes, the Conference Organisers:

OUBS President Alexander Johnston

OUBS Secretary Sophia Miller

OUBS Treasurer Duncan Antich

Schedule of Papers

Session 1: Saturday, 11.30–13.00

Panel 1a: The Water Cycle (Chair – Duncan Antich)

‘Exploring Monastic Water Systems: A Preliminary Study from the Kyrenia Range’ – Mehmetcan Soyluoğlu (The Cyprus Institute)

‘Sacred Waters: Fish, Fishermen, and the Baptism of Christ in Cretan Churches’ – Nicolyna Enriquez (University of California, Los Angeles)

‘Mollusk Materiality: Maritime Encounters at the Euphrasian Basilica in Poreč, Croatia’ – Zoe Appleby (Case Western Reserve University)

Panel 1b: Nature in Verse and Liturgy (Chair – Tarah Rosendahl)

‘St. Demetrius and the Enduring Earthquake’ – John Elliott Clark (Kellogg College, University of Oxford)

‘Wolves, Waves and Thunderstorms: Nature and Suffering in Nikolaos Mouzalon’s poem’ – Kyriakos Costa (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens)

‘“Rise, oh Nile!”: Ritualization of the Flooding of the Nile in medieval Melkite Egyptian euchologia’ – Achraf Brahim (University of Vienna)

Session 2: Saturday, 14.00–15.30

Panel 2a: Transition – Climatic shifts from the 4th-9th centuries (Chair: Marcus Wells)

‘Seasonal Patterns in the Archaeological, Palaeoclimatological, and Historic Records of Hunnic Mobility within the Byzantine Empire in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries’ – Mel G. Smith (University of Cambridge)

‘Nobody Wants to be Here, and Nobody Wants to Leave: Climate and Resilience in the 6th Century’ – Andrew McNey (Reuben College, University of Oxford)

‘Non-Elite Earthquake Responses in Lechaion Basilica, Corinthia (6th to 9th c.CE)’ – James Razumoff (University of Virginia)

Panel 2b: The Literary climate (Chair: Gabriel Clisham)

‘Cassiodorus’ natural digressions and their role in Ostrogothic politics’ – Ethan Chilcott (Pembroke College, University of Oxford)

‘Fearful Heights, Helpful Thieves, and Wild Honey. Representations of Mountains and Mountain Peoples in Late Byzantine Epistolography’ – Guillaume Bidaut (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne)

‘Reconsidering the Bulgarian Revolt of 1040: Environmental Perspectives’ – Findlay Willis (Pembroke College, University of Oxford)

Session 3: Saturday, 16.00–17.30

Panel 3a: Paradise (Chair: Sophia Miller)

‘Ephrem’s Eternal Landscape: Natural Imagery in the Hymns on Paradise’ – Katherine Painter (Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford)

‘Arboreal Analogues: Trees as Spiritual Participants in a North African Baptismal Font’ – Luke Hester (Case Western Reserve University)

‘Fruitful Trees, Lush Vegetation, and Unified Weather Conditions: Depicting Nature in Byzantine Art of Crete Under Venetian Rule’ – Polymnia Synodinou (University of Crete)

Panel 3b: Practicality (Chair: Alexander Johnston)

‘Illuminating the Byzantine Frontier: A Geospatial Study of Environmental Considerations in the Ninth Century Fire Beacon Network’ – Annalise Whalen (University of Central Florida)

‘The Impact of Natural and Environmental Factors on Defense Structures: The Walls of Bursa’ – Egemen Deniz (Bursa Uludağ University)

‘In the Making of the Water Heritage: Picturing the Valens Aqueduct in Early Modern Constantinople’ – Fatma Sarıkaya-Işık (Middle East Technical University)

Session 4: Sunday, 11.30–12.30

Panel 4a: Landuse and Landscape (Chair: Eleanore Debs)

‘Modeling Mobility in the Chora: Rural Christianity and Sacred Landscape in Late Antique Aphrodisias’ – Elizabeth R. Davis (Brown University)

‘Use of Marginal Land: The Expansion of Settlements and Use of the Environment in the Upper Western Galilee in Late Antiquity’ – Matthew Peters (Keble College, University of Oxford)

Panel 4b: The Late Antique Little Ice Age (Chair: Findlay Willis)

‘Examining the Late Antique Little Ice Age’s Impact on Negev Viticulture Through 19th Century European Analogues’ – Molly A. Stevens (Independent Scholar)

‘‘The Ister is foreign to you’: climate and warfare behind and beyond the Danube at the end of Late Antiquity’ – Carlo Alberto Rebottini (University of San Marino)

Session 5: Sunday, 13.30–14.30

Panel 5a: Nature and Art between two faiths (Chair: Michael Hughes)

‘Crosses in early Islam’ – Gabriel Fowden (Independent Scholar)

‘Mosaics as Micro-Cosmos: Nature and Identity in Christian and Islamic Mosaics of the Seventh-and Eighth-Century Levant’ – Madeleine Duperouzel (Hertford College, University of Oxford)

Panel 5b: Grapes and Bees (Chair: Ethan Chilcott)

‘Teeming the Divine: Art and Architecture of Sacred Spaces as Environmental Amplifications in 9th-10th century Cappadocia’ Maria Shevelkina (Stanford University)

‘Bees and Wasps in Byzantine Hagiography’ – Ayşenur Mulla-Topcan (University of Silesia in Katowice)

From the Archive: The Call for Papers

We are pleased to announce the call for papers for the 27th Annual Oxford University Byzantine Society International Graduate Conference on the 1st-2nd March 2025. Papers are invited to tackle the ‘environment’ of the Late Antique and Byzantine world (very broadly defined). For the call for papers, and for details on how to submit an abstract for consideration for the conference, please see below.

In recent decades, the global community has taken more and more of an active and serious interest in the environment and climate system in which we live. Scholars of Byzantium and Late Antiquity have likewise begun to apply environmental lenses to their research, and have come away with a number of new and exciting perspectives. From scientific analysis of the climatic shifts that occurred throughout the period on both macro and micro scales, to revisionist views of already well-trodden events, these new perspectives are greatly contributing to our field.

The framework of ‘the environment’ here can be applied very broadly, touching on any aspect of the natural world, with novel and imaginative approaches to the notion being strongly encouraged. Some suggestions by the Oxford University Byzantine Society for how this topic might be treated include:

- The Analytical – Pollen analysis, dendrochronology, ice cores, and everything in-between; the historical significance of this data and what it can tell us

- The Political and Economic – Climate’s impact on internal and external politics, adaptions in trade and policy, effects on particular military campaigns

- The Cultural – Changes in attitudes and output as a result of shifting climates, nature’s representation and role in literature

- The Societal – Movement of people and changes to the social order as a result of climatic change; variations in the impact of climate change depending on class or occupation, regional adaptations to specific micro-climates

- The Religious – Responses to unusual weather events and interpretations of changing climates by different religious communities; religious attitudes towards nature and man’s place in it

- The Artistic and Architectural – Environmentally-focused artwork and its uses; the use of landscapes both natural and man-made; changes in design or materials in response to changing climates

- The Archaeological – Changing use of the land during periods of climatic shift; abandonment and re-settlement due to changing weather or specific events

- The Historiographical – How environmental factors have evolved over time in scholarship

Please send an abstract of no more than 250 words, with a short academic biography written in the third person, to the Oxford University Byzantine Society at byzantine.society@gmail.com by Friday 29th November 2024.

Papers should be twenty minutes in length and may be delivered in English or French. As with previous conferences, selected papers will be published in an edited volume, peer-reviewed by specialists in the field. Submissions should aim to be as close to the theme as possible in their abstract and paper, especially if they wish to be considered for inclusion in the edited volume. Nevertheless, all submissions are warmly invited.

The conference will have a hybrid format, with papers delivered at the Oxford University History Faculty and livestreamed online for a remote audience. Accepted speakers should expect and plan to participate in person.

Header image: © Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Photography by Neil Greentree