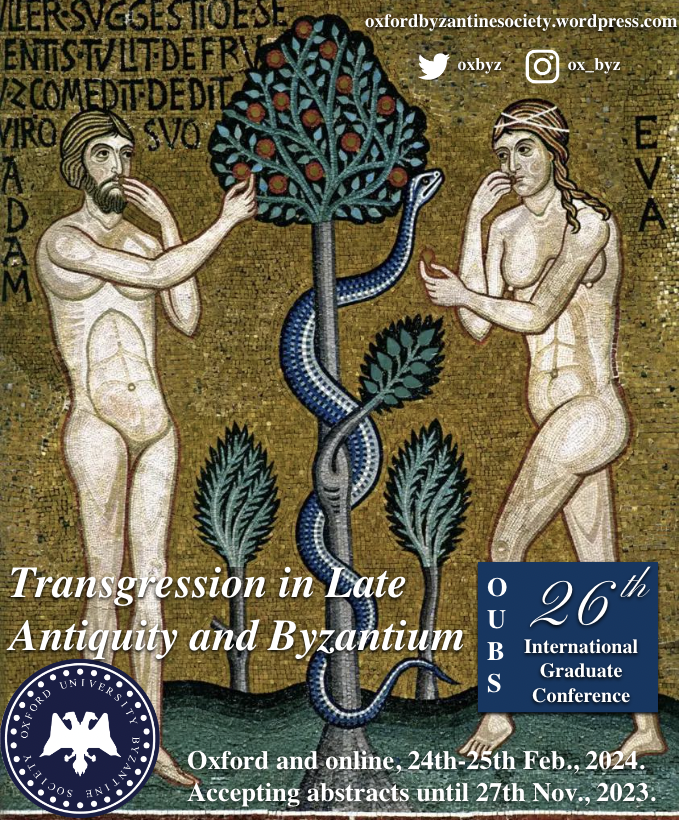

26th International Graduate Conference of the Oxford University Byzantine Society:

Transgression in Late Antiquity and Byzantium

24th-25th February 2024, Oxford

We are pleased to announce the call for papers for the 26th Annual Oxford University Byzantine Society International Graduate Conference on the 24th – 25th February, 2024. Papers are invited to approach the theme of ‘Transgression’ within the Late Antique and Byzantine world (very broadly defined). For the call for papers, and for details on how to submit an abstract for consideration for the conference, please see below.

‘Seduced by love for you, I went mad, Aquilina … she, smouldering, not any less love-struck than me, would wander throughout the house … love alone became her heart’s obsession … Her tutor chased me. Her grim mother guarded her … they scrutinised our eyes and nods, and colouring that tends to signal thoughts … soon both of us began to seek out times and places to converse with eyebrows and our eyes, to dupe the guards, to put a foot down gingerly, and in the night to run without a sound. Our fiery hearts ignite a doubled frenzied passion, and so an anguish mixed with love rages … Boethius, offering aid, pacifies her parents’ hearts with “gifts” and lures soft touches to my goal with cash. Blind love of money overcomes parental love; they both begin to love their daughter’s guilt. They give us room for secret sins … yet wickedness, when permitted, becomes worthless, and lust for the deed languishes … so a sanctioned license stole my zeal for sinning, and even longing for such things departed. The two of us split up, miserable and dissatisfied in equal measure …’

Maximianus, Elegies, 3 (adapted tr. Juster)

The Late Antique and Byzantine world was a medley of various modes of transgression: orthodoxy and heresy; borders and breakthroughs; laws and outlaws; taxes and tax evaders; praise and polemic; sacred and profane; idealism and pragmatism; rule and riot. Whether amidst the ‘purple’, the pulpits, or the populace, transgression formed an almost unavoidable aspect of daily life for individuals across the empire and its neighbouring regions. The framework of ‘Transgression’ then is very widely applicable, with novel and imaginative approaches to the notion being strongly encouraged. In tandem with seeking as broad a range of relevant papers as possible within Late Antique and Byzantine Studies, some suggestions by the Oxford University Byzantine Society for how this topic might be treated include:

· The Literary – deviance from established genres, styles or tropes; bold exploration of new artistic territory; penned subversiveness against higher authorities (whether discreetly or openly broadcasted); dissemination of literature beyond expected limits.

· The Political – usurpers, revolts, breakaway regions, court intrigue, plots and coups; contravention of aristocratic or political hierarchies and their expectations; royal ceremonial and its changes, or imperial self-promotion and propaganda seeking to rupture or distort the truth.

· The Geopolitical – stepping beyond or breaking through boundaries and borders, including invasions, expeditions, trade (whether in commodities or ideas), movements of peoples and tribes, or even the establishment of settlements and colonies.

· The Religious and Spiritual – ‘Heresy’, sectarianism, paganism, esotericism, magic, and more; and, in reverse, all discussion of ‘Orthodoxy’, which so defined itself in opposition to that which it considered transgressive; monastic orders and practices (anchoritic and coenobitic) and their associated canons, themselves intertwined and explicative of what was deemed prohibited; holy fools and other individuals perceived as deviant from typical holy men.

· The Social and Sartorial – gender-based expectations in public and private; the contravention (or enforcement) of status or class boundaries; proscribed or vagrant habits of dress, jewellery, fabrics, etc.

· The Linguistic – transmission of language elements across regional borders or cultures, including loan words, dialectic and stylistic influences, as well as other topics concerning lingual crossover and interaction.

· The Artistic and Architectural – the practice of spolia; the spread and mix of architectural styles from differing regions and cultures; cross-confessionalism evident from the layout or architecture of religious edifices; variant depictions of Christ and other holy figures; iconoclasm.

· The Legal – whether it be examination of imperial law codes and their effectiveness or more localised disputes testified to by preserved papyri, all discussion concerning legal affairs naturally involves assessing transgressive behaviour and how it was viewed and handled.

· It could even be that your paper’s relevance to ‘Transgression’ consists in its breaking out from scholarly consensus in a notable way!

Please send an abstract of no more than 250 words, with a short academic biography written in the third person, to the Oxford University Byzantine Society at byzantine.society@gmail.com by Monday 27th November 2023. Papers should be twenty minutes in length and may be delivered in English or French. As with previous conferences, selected papers will be published in an edited volume, peer-reviewed by specialists in the field. Submissions should aim to be as close to the theme as possible in their abstract and paper, especially if they wish to be considered for inclusion in the edited volume. Nevertheless, all submissions are warmly invited.

The conference will have a hybrid format, with papers delivered at the Oxford University History Faculty and livestreamed for a remote audience. Accepted speakers should expect to participate in person.