5th May 2021 will see the launch of the Taylor digital edition of MS Bodl. 972, a sixteenth-century copy of Arnold von Harff’s Reisebericht or travel account. This edition is the fruit of much hard work from Agnes Hilger and Eva Neufeind, who spent last term in Oxford as Erasmus interns with Henrike Lähnemann. In anticipation, we’ve put together a mini series of posts across various Oxford and Oxford-adjacent blogs. The first, which you can read on the Oxford Medieval Studies blog, was an introduction from Mary Boyle to Arnold von Harff and his literary context. The second, posted jointly on Teaching the Codex and Oxford’s History of the Book blog, was produced by Aysha Strachan, and gave us an insight into the manuscript’s journey to Oxford. The third post in the series comes from Josephine Bewerunge and Marlene Schilling, and it takes Arnold von Harff’s account as a starting point to explore the biography of a female pilgrim, Dorothea von Montau. Read on to find out more!

by Josephine Bewerunge & Marlene Schilling

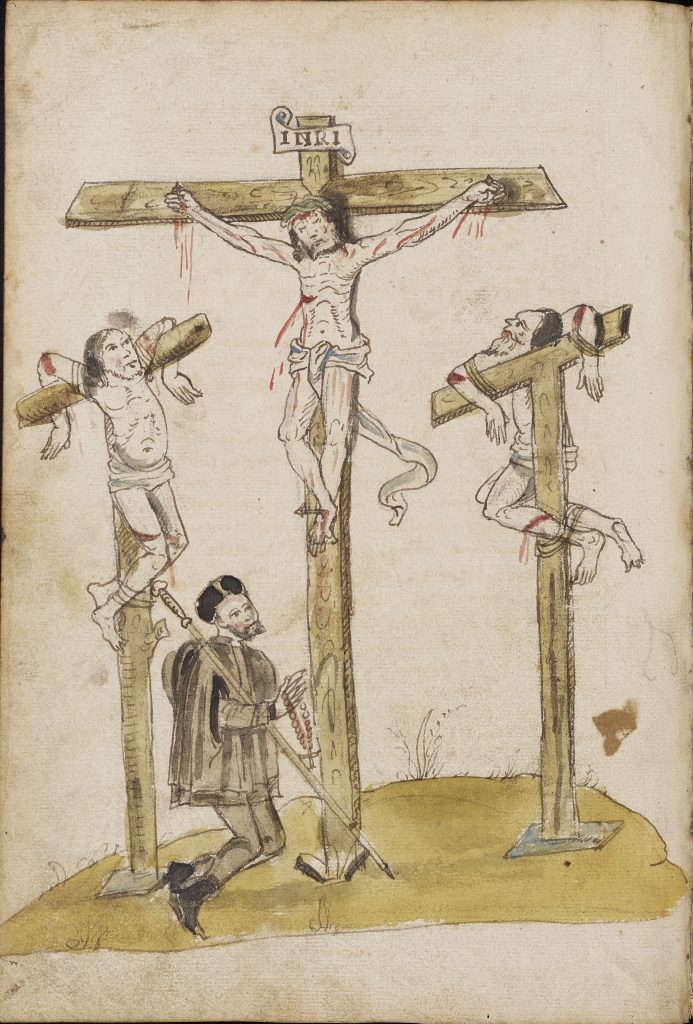

When it comes to pilgrimage, the journey is most definitely the destination. This becomes very clear when looking at literary descriptions of religious travel: in the report of his three-year-long journey, Arnold von Harff describes his travels around Europe, Palestine and the Ottoman Empire between 1496 and 1499. The book features detailed descriptions of the culture, the people and the places he has visited, glossaries and alphabets of several different languages, drawings, and even an overview of the distance between each destination. In the end, Arnold gives a most crucial piece of advice to anyone who might want to follow in his footsteps: to take care of one’s belongings so they don’t get stolen on the way.

Arnold’s report reads like an adventure, suggesting that he strove for acclaim from his readership. Yet, the religious motivation for his travels can seem to fade into the background. So why not take a look at a different pilgrim whose journey was all about connecting with God, like Dorothea von Montau (1347-1394)? As a modest and pious woman, she did not have much in common with the self-consciously masculine aristocratic Arnold – except for the fact that her pilgrimages, too, have been written about: her life as a mystic and recluse is described in her biography, which includes several accounts of religious travel. In terms of perspective, aim and context, the writings about her life differ from Arnold’s travel report in every possible way.

The differences actually begin with the texts’ purposes: while Arnold describes the things he has – allegedly – seen with his own eyes during his travels, the vernacular biography, written by Dorothea’s confessor Johannes Marienwerder was intended to enhance her popularity among the local Teutonic Order community during her canonisation process, which was initiated shortly after her death in 1394. Although it claims to be based on Dorothea’s own accounts about her life which she shared with her confessor during her last years, one has to keep in mind that the text presents a literary construct of Dorothea’s life and of Dorothea herself, in the way a male theologian imagined an ideal pious woman.

Still, we can have something of a look at the female perspective on pilgrimage – as we’ve mentioned already, Dorothea was on the road quite a lot. Amongst other destinations, she travelled to Aachen, Rome and the Swiss Einsiedeln. A pilgrimage does not simply end at its main site though, and the way back might be just as difficult and testing. The distant third-person narrator describes Dorothea’s way back home from her pilgrimage to Einsiedeln as a very straining journey. She travels with both her senile husband and their young daughter. And just like a modern-day mum on vacation, she is the one holding it all together.

pilgrimages even today

While her journey is surely an adventure, it is very different from Arnold’s. Besides the challenging conditions of the journey (which are best described by the words God himself uses in the text: wassir, kot und sne [water, faeces and snow]), Dorothea’s biggest struggle is looking after her family. She is the one who carries her husband’s luggage throughout their journey and who washes her family’s clothing at night, while also protecting their belongings from theft, since her husband is too frail to do that. Her hardships are underlined by the narrator’s frequent usage of the word field ‘suffering’ and the strong emphasis on Dorothea’s loneliness and tiredness throughout this episode:

des nachtis […] slief der man herte von mudikeit, und dy muste wachen, das sy icht vorlorn das ire und beschediget worden libes und gutes, alleyne sy ouch wol hette ru und slofes bedorft

at night her husband slept deeply because of his fatigue and she had to keep watch for them to not lose their possessions and to not be physically harmed, but she would have needed rest and sleep as well

Only God helps and protects her and raises her up when needed. This very strong connection between Dorothea and God is another difference from Arnold’s reports: while Arnold only asks God for his help during his travels, we actually see God’s help in action in Dorothea’s case. She considers him a spiritual groom, which draws a sharp contrast to her real-life husband, who is only adding to her distress. Ultimately, the way she bears her misery with the help of her steadfast trust in God is what actually makes her worthy to be a saint – the main point the biography intends to prove to the reader.

Dorothea’s central role as a strong woman among incapable men promotes an interesting gender dynamic. Transgressing the stereotypes of female passivity, she takes on the role of family protector – even saving her family’s life single-handedly. At one point during the journey, they have to cross a frozen lake and manage to travel with a horse-drawn sleigh. All of a sudden, a slight cracking noise indicates a catastrophe: the ice starts to break under the weight and the carriage falls through. Whilst the sleigh driver, his companion and her husband are startled and remain passive, Dorothea acts like a true hero. The narrator describes how she quickly grabs their luggage with one hand and her daughter with the other and jumps off the sleigh. Because her husband is – once again – unable to act in this situation of great danger, Dorothea has to come to his rescue. She grabs him by his feet and pulls him out of the water. This time, it is her daughter who points out divine intervention behind these events: she insists that it was in fact the Blessed Virgin Mary who saved her (because how else would you explain a woman so strong and resilient?).

Having heard about Dorothea’s journey, the travels of Arnold von Harff sound more like an adventurous holiday and what is more, he was clever enough to travel without dependents. Apart from the topic of pilgrimage, they do not seem to have much in common. However, the accounts share one major similarity: they are written to inspire. Dorothea’s endurance and faith are exemplary for anyone who wants to lead a godlier life. As for Arnold, his report can serve as a guidance for those who want to undertake a similar journey – or as an inspiration for those who want to imagine one – or even, maybe, for those who just want to pretend they did. After all, travelling, just like writing, is just a matter of perspective.

Bibliography

- Toeppen, Max (Ed.): Das Leben der heiligen Dorothea von Johannes Marienwerder. Scriptores rerum Prussicarum. (Die Geschichtsquellen der preußischen Vorzeit). Vol. 2. Leipzig 1863, pp. 179–374.

- Translation into English: Stargardt, Ute. The Life of Dorothea Von Montau, a Fourteenth-Century Recluse. Mellen, 1997.

Image Permissions

- Wikimedia Commons (Chapel of Blessed Dorothea in Kwidzyn Cathedral.): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-SA 3.0). Author: Kudak.

- Wikimedia Commons (Kwidzyn, cathedral seen from Słowiańska Str., from eastern side): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-SA 3.0). Author: Pko.

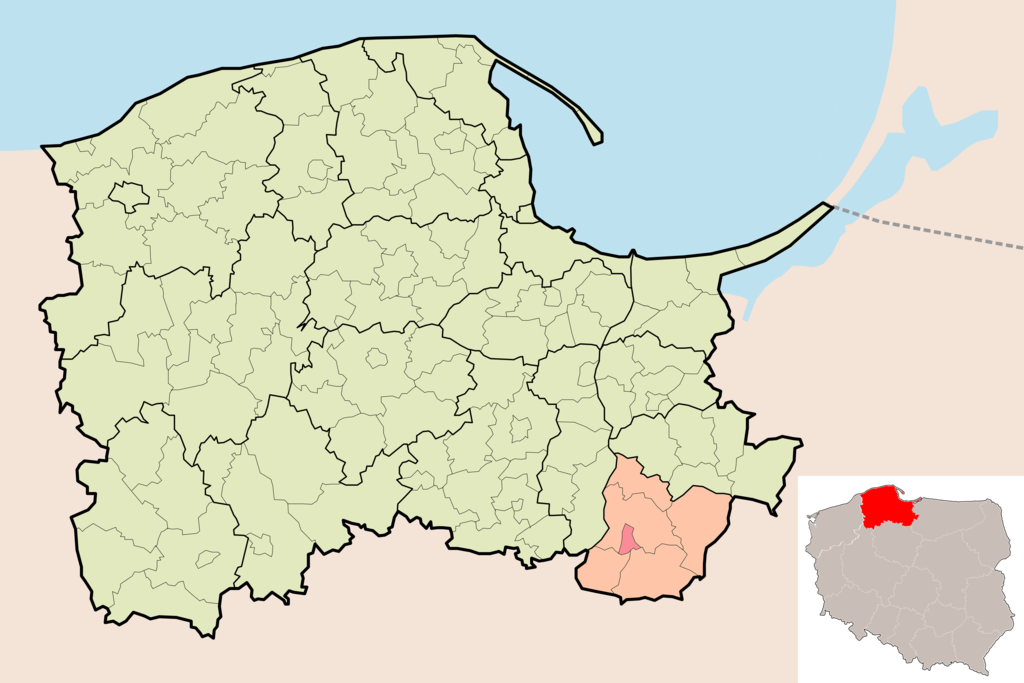

- Wikimedia Commons (Map – PL – powiat kwidzynski – miasto Kwidzyn): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-SA 3.0). Author: Michiel1972.

- Wikimedia Commons (Einsiedeln-Katzenstrick: Just Einsiedeln, really.): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0). Author: Steph-Fuchs.

- Wikimedia Commons (Ołtarz w celi bł. Doroty z Mątowów w katedrze w Kwidzynie): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic License (CC BY-SA 2.5). Author: Marcin n.

About the authors

Josephine Bewerunge and Marlene Schilling are both reading for the MSt in Modern Languages (German) at the University of Oxford in the academic year 2020/21. This blogpost is based on their joint presentation for the Medieval German Graduate Seminar in Hilary Term 2021.