We have made it, at long last, to the end of another Hilary term – but the events don’t stop coming! Please find below another week full of medieval events for you to enjoy, and an ever-increasing list of future opportunities. NB: the Maison Française d’Oxford lecture this Tuesday has had to move earlier and is now at 12:00.

Monday

- French Palaeography Manuscript Reading Group – 10:30, Weston Library.

- Seminar in Palaeography and Manuscript studies – 2:15, Weston Library. Seamus Dwyer (Cambridge) will speak on ‘Pen-Flourishing and the Boundaries of Meaning’.

- Medieval Archaeology Seminar – 3:00, Archaeology Faculty. Eugene Costello will be speaking on ‘Exploring the expansion of pastoral farming in northern Europe’s uplands, c.1200-1600’.

- Medieval History Seminar – 5:00, All Souls College. Nick Evans (Birkbeck) “Cowries, Cloth and Coins: Currency in Medieval Economic Anthropology”.

- Theory and Play: Comparative Medievalisms – 5.15, Lady Margaret Hall.

Tuesday

- Europe in the Later Middle Ages Seminar – 2:00, New Seminar Room, St John’s College. Mike Carr (Edinburgh) will be speaking on ‘Popes, Ambassadors and Falcons: Trade and Diplomacy between Latin Europe and the Mamluk Sultanate in the Fourteenth Century’.

- Latin Palaeography Manuscript Reading Group – 2:00, Weston Library (Horton Room). Those who are interested can contact the convenor, Laure Miolo.

- Maison Française d’Oxford lectures: ‘Children in the Middle Ages’ – 12:00, Maison Française. NB. the new, earlier, time.

- Maghrib History Seminar: “Reading the Qurʾān across the Mediterranean: Toward a Maghribī School of Tafsīr in Early Islam” – 5:00, The Queen’s College.

- Medieval Church and Culture, theme: TRANSLATION(S) – tea and coffee from 5:00, Harris Manchester College. Celeste Pan (Balliol) will be speaking on ‘Some issues of translation in an illuminated Hebrew bible manuscript from medieval Brussels (Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibl., Cod. Levy 19)’.

- Old English Hagiography Reading Group – 5:15, Jesus College Memorial Room.

- Church Historian Pub Night – 6:00 at the Chequers Inn. Contact Rachel Cresswell.

Wednesday

- History and Materiality of the Book Seminar series – 2:15, Weston Library. Matthew Holford and Laure Miolo will be speaking on ‘Text identification’.

- Older Scots Reading Group – 2:30, Room 30.401 (Humanities Centre). Palyce of Honour, Thyrd Part, ll. 1288-2142; Palyce of Honour, Dedication, ll. 2142-2169.

- The Medieval Latin Documentary Palaeography Reading Group – 4:00, online.

- Islamic Studies Seminar – 5:00, Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Professor Sheilagh Ogilvie (University of Oxford) will speak on ‘Leviathan’s Health: State Capacity and Epidemics from the Black Death to Covid’.

- Late Antique and Byzantine Seminar – 5:00, Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies. Nathan Websdale (Oxford) will be speaking on ‘Unbecoming Roman: Performative Ethnicity and Panspermía in the Byzantine World c.1190-1235’.

- eCatalogus+: A Digital Tool for the Automated Study of Latin Manuscripts (Liturgical Case Studies) – 5:00, Weston Library. More infomation here.

- Lydgate Book Club – Weston manuscript visit with Laure Miolo. Meet 3:50pm at the Weston lockers for a 4pm start. Please email Shaw Worth for any information.

Thursday

- Middle English Reading Group (MERG) – 11:00, Lincoln College, Beckington Room. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Medieval Women’s Writing Research Seminar – 4:00, Somerville College. Making and Breaking Connections, including letters sent by Hildegard von Bingen and Catherine of Lancaster, queen of Castile.

- Seminars in Medieval and Renaissance Music – 5:00, online. Elisabeth Giselbrecht, Louisa Hunter-Bradley and Katie McKeogh (King’s College London) will be speaking on ‘No two books are the same. Interactions with early printed music and the people behind them’.

- Celtic Seminar – 5:15, hybrid. Eleanor Stephenson (Cambridge) will be speaking on ‘Landscapes of Extraction: Philippe de Loutherbourg and the Morris Family’s Copper Works, Swansea’.

- Medieval Visual Culture Seminar – 5:00, St Catherine’ College. Emily Guerry (University of Oxford) will be speaking on ‘Silver trees and pearl crosses: Franco-Mongolian diplomacy and cultural exchange in thirteenth-century Karakorum’.

- The Khalili Research Centre For the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East: Research Seminar – 5:15, The Khalili Research Centre. Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis (Freie Universität, Berlin) will be speaking on ‘A Greek-Orthodox monastery in the desert: Mount Sinai and the material culture of its Arabic (and Islamic) manuscripts’.

Friday

- Medievalist Coffee Morning – Friday 10:30, Visiting Scholars Centre (Weston Library). All welcome, coffee and insight into special collections provided. This week, Jana Lammerding will speak on the representation of witches in the Douce Collection.

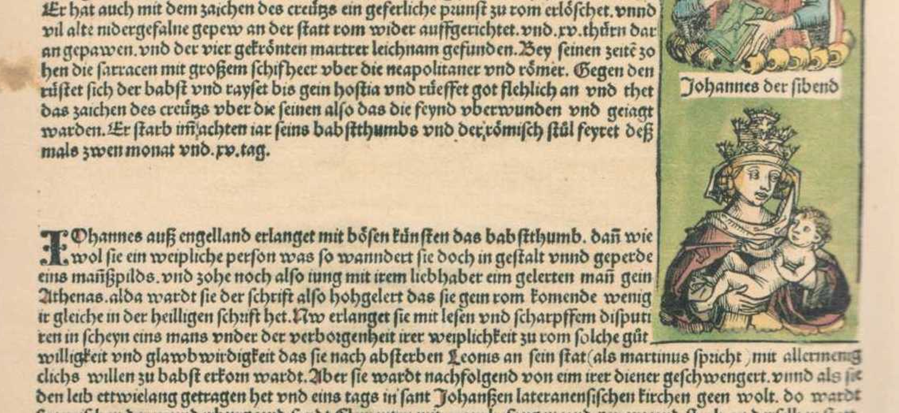

- The History of the Bible: From Manuscripts to Print – 12:00, Visiting Scholars Centre at the Weston Library. Week 8: The Bible printed. Places are limited. To register interest and secure a place, please contact Péter Tóth.

- Exploring Medieval Oxford through Surviving Archives – 2:00, Weston Library (Horton Room). Those who are interested can contact the convenor, Laure Miolo.

- EMBI ‘New Books: A Celebration’. – 4:30, Schwartzman Room 421. Helena Hamerow and Conor O’Brien will talk informally about the process of researching and writing the projects that they have both just published, and we will also hear some reflections on being a postdoctoral researcher on a major project such as the ERC-funded grant for FeedSax. End-of-term drinks in Jude the Obscure, Walton St.

- Oxford Medieval Manuscript Group – 5:00, John Roberts Room at Merton College. Julian Harison (Curator, British Library) will be speaking on ‘Sir Robert Cotton and Oxford’.

Opportunities and Reminders

- CfP for the Oxford Medieval Graduate Conference 2026: Sounds & Silence, taking place on April 23–24, 2026. More information here.

- Register for the Reading Graduate conference ‘Locational Lives: Medieval Experience in Town and Country’. More information

- CfP: Borders, Boundaries and Barriers: Real and Imagined in the Middle Ages. More information here.

- Registration is still open for the Medieval Insular Romance Conference, ‘Moving Medieval Romance’. 8–10 April 2026, St Hugh’s College, Oxford.

- Dies Legibiles, Smith College’s undergraduate journal of Medieval Studies, is looking for submissions for the 2025-2026 edition, deadline 3 March 2026 (website)

- Submission welcome to the journal Manuscript and Text Cultures.

- Doctoral studentship on Carolingian Latin poetry (Toronto-Melbourne).

- CfP: 20th Annual MEMSA Conference: Connection, Conversation, Contention: Encounters in the Medieval and Early Modern World – deadline 9 March 2026

- CfP: Imagining Britain: Postgraduate and Early Career Research in British and Irish Art, 9 June 2026. Deadline 9th March.

- CfP: Forgotten Libraries: Lost, Dispersed, and Marginalised Manuscript Collections – deadline 14 March 2026

- CfP: Crossing Intellectual Boundaries in English Legal History. Proposals for papers should be no more than 400 words and should be sent to Ciara Kennefick and Ian Williams by 5pm on 23 March 2026.

- CfP: Gender and Medieval Studies conference 2026: Gender and Creativity. The conference will take place at University College, Oxford, 8-10 September. Deadline 13 April.

- CfP: Summer Conference of the Ecclesiastical History Society on the theme “The Church and Race. Deadline 15 April.

- Call for submissions for a special issue of Public Humanities journal on the topic ‘Creating the Medieval Now.’ Edited by Laura Varnam and Eleanor Barraclough. Short essays of 2,000-3,000 words, due 1 May 2026, by medievalists who are also creative practitioners.

- CfP: The Body in History. Deadline 6th July.

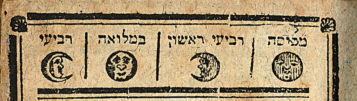

- Save the date – 500 Years of Yiddish Printing: Symposium: 4–6 October 2026 | University of Oxford, Oxford, UK