Wishing all readers a Happy New Year! Post first published on the blog about the Medingen Manuscripts

Sending Christ in the Heart from the Convent of Lüne

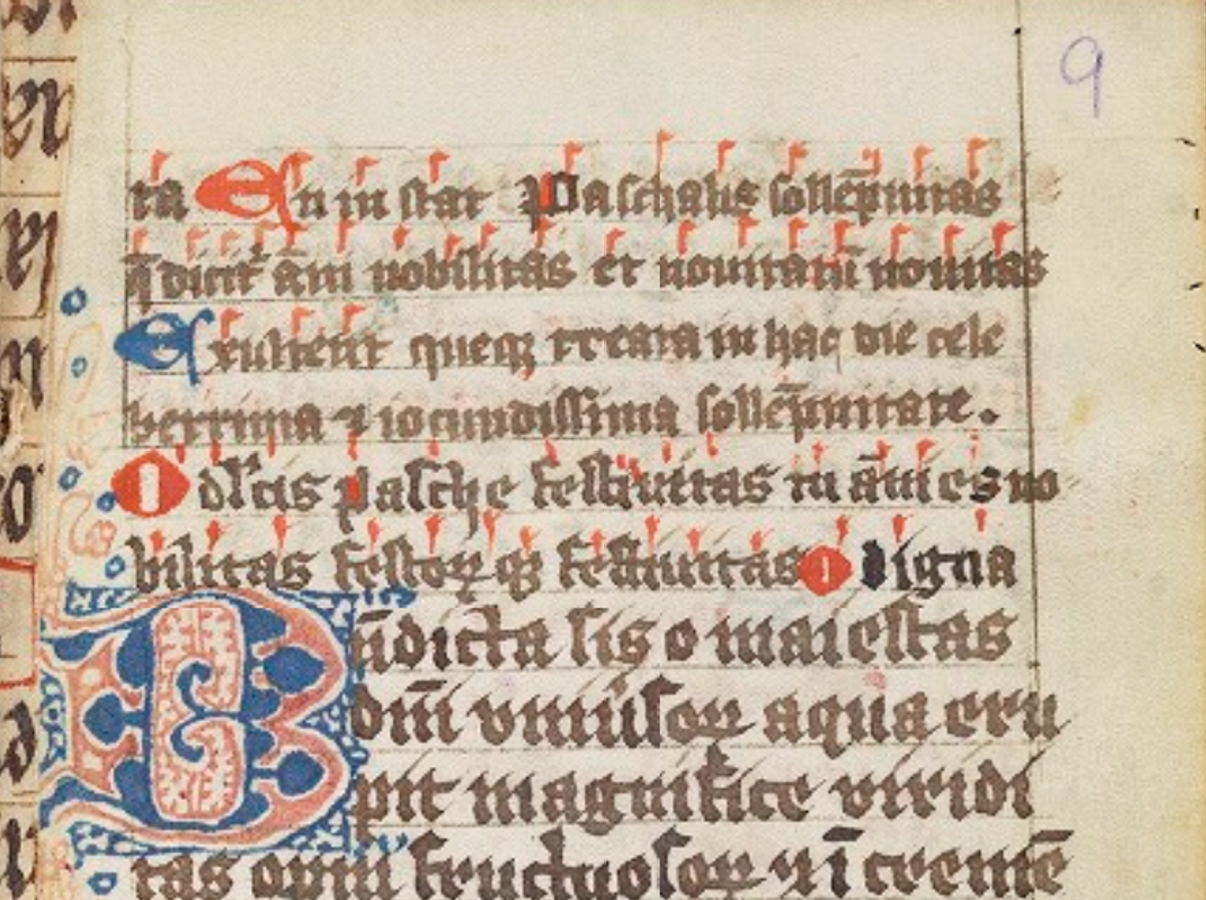

On a New Year’s Eve in the first half of the 1480s, two young nuns in the convent of Lüne sat down to write to a woman they admired (letter no. 260 in the first letter book, edited by Eva Schlotheuber and Henrike Lähnemann). Their addressee, the lay sister (conversa) Elisabeth Bockes, had come from the neighboring convent of Ebstorf a few years earlier to help implement the monastic reform in Lüne. She had carried heavy responsibilities pro reformatione, and earned not only a glowing entry in the convent chronicle but personal gratitude from the younger sisters who had grown up under her care. They open their New Year’s letter with warm words:

Alderleveste Elisabeth Bockesken, we danket juwer leve lefliken unde fruntliken vor alle woldath, truwe unde leve, de gy vaken unde vele by us hebbet bewiset van usen junghen iaren wente an dessen dach, sunderken de wile, de gy hir myd us weren pro reformatione, do gy mannighen swaren arbeyt myd us hadden, des we juk nummer to vullen danken kond,

Dearest beloved Elisabeth Bockes, we thank your love kindly and friendly for all the good deeds, loyalty, and love that you have shown to us often and much, from our youth up to this day, especially during the time when you were here with us for the reform, when you had many heavy labours with us, for which we can never thank you enough.

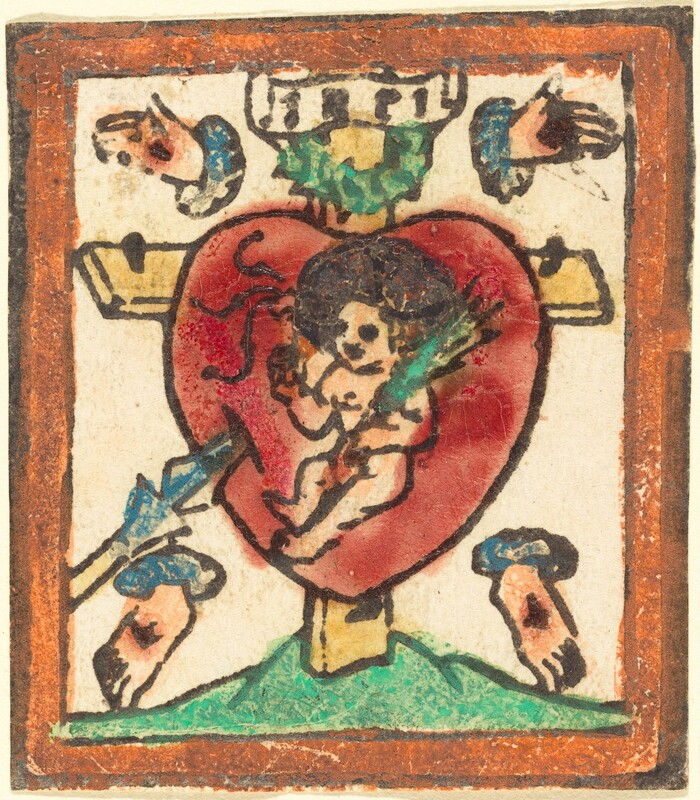

The letter is, very explicitly, about reform: a moment when enclosure, obedience, and common life were being reshaped. But it is also about something more intimate: gratitude, affection across convent walls, and the small things one sends to mark the turning of the year. Along with the letter, the writers enclose two lengths of cloth and, crucially, a little devotional image—a bladeken, a “little leaf”—depicting the Christ Child enthroned inside Christ’s heart. They do not simply mention the image; they script how Elisabeth should use it:

Hirumme, alderleveste, sende we juk an rechter leve en luttik hilgenbladeken, dar vynde gy inne ghemalet dat benediede, sote, gotlike herte uses leven salichmakeres, dat he umme user leve willen openen led myd dem scharpen spere; unde bynnen in dessem herteken syd dat alderschoneste begherlikeste kyndeken Jesus, dat mote juk gheven dor syne hilgen mynscheyt en nye, vrolick, sunt, salich iar; unde allent, wes gy begherende synt, beyde an dem lyve unde an der sele, dat gy sughen moten ute synem honnichvletenden herten den hemmelschen invlote syner gotliken gnade unde soticheyt, so vullenkomelken, dat gy dar ghansliken moten inne vordrunken werden,

Therefore, dearest, we send you, in true love, a little devotional leaf, wherein you will find painted the blessed, sweet, divine heart of our dear Saviour, which he let be opened for love of us with the sharp spear; and within this little heart sits the most beautiful, most desirable little child Jesus, who may grant you through his holy humanity a new, joyful, healthy, blessed year; and everything you desire, both for body and for soul, so that you may draw from his honey-flowing heart the heavenly influx of his divine grace and sweetness, so fully that you might be completely intoxicated by it.

At the end of the letter, the two little sheep in Lüne beg Elisabeth not to forget them but to remember them in prayer. The small image is thus at once a New Year’s gift, a tool for personal devotion, and a material reminder of the bond forged through reform. This is where I want to begin: with a New Year’s greeting that looks, at first glance, not so different from our own good wishes for health, affectionate diminutives, a token of friendship, but that centers on a pierced heart and a child-king seated within it. What happens if we take these New Year’s letters, their devotional images, and their language of hearts and gifts as a starting point for thinking about the intellectual and emotional life of late medieval nuns?

The Letters from the Benedictine Convent of Lüne: Gifts Between Convents

The letter discussed above belongs to the wider “nuns’ networks” of northern Germany. The most important sources for this world are the three Lüne letter-books, which together preserve almost 1,800 letters written or received between roughly 1460 and 1555. These letters cross convent boundaries and weave Lüne into a network of the other Lüneburg convents Ebstorf, Isenhagen, Medingen, Walsrode, and Wienhausen,as well as into circles of lay relatives in town. Many are tied to specific occasions: congratulatory letters for nun’s coronations or birthdays, words of consolation after the death of a convent sister or family member, and seasonal greetings for Christmas and, especially, the New Year.

In the Lüne letters, New Year stands on its own as the key moment for exchanging wishes and tokens (e.g., letter nos. 181–183, 200, 205, 226, 254, 260–262). The emphasis falls less on surprise or abundance than on reciprocity and remembrance—what anthropologists would later call the logic of gift and counter-gift. A gift is rarely a unilateral act; it carries an implicit call to respond, not necessarily with something of equal material value, but with prayer, affection, or loyalty. To modern readers, Christmas is the gift-saturated feast and New Year’s presents are at best an afterthought. In fifteenth-century central Europe, however, the balance often tipped the other way. The practice of New Year’s gifts has deep roots: already in ancient Rome people marked the Kalendae Ianuariae by exchanging strenae—figs, dates, honey, and small sums of money—as good omens for the year ahead. Medieval and early modern sources across Europe still show New Year’s gifts circulating between rulers and courtiers, householders and servants, parents and children. Only gradually, especially from the Reformation onward, did Christmas Eve emerge as a rival occasion for giving.

Many of these Lüne letters explicitly mention small devotional images. Hs. 15, one of the letter-books, refers to about thirty-five such pictures on its own. The letters themselves, however, no longer survive with their original enclosures. The little leaves they describe were meant to be handled, carried, pinned up, kissed, and eventually worn away. To reconstruct what Elisabeth and other recipients might actually have held in their hands, we have to look instead to surviving visual material from neighbouring convents.

At the Cistercian convent of Wienhausen, not far from Lüne, the lifting of the floorboards in the 1950s uncovered around a hundred small devotional images hidden under the choir stalls: tiny sheets of parchment depicting, among other things, the Holy Face, the Risen Christ, the Five Wounds, and the Christ Child seated in a heart. These are precisely the motifs that recur in the Lüne letters. One surviving Wienhausen image shows a Christ Child painted in brown ink inside a red heart, framed by a red inscription. Elsewhere in the convent, a wall painting in the upper west wing of the cloister presents the Heart of Jesus with the Christ Child within, holding the scourging instrument; above hovers a dove and, above that, a scroll inscribed The Christ Child. It is not far-fetched to imagine that the devotional image sent to Elisabeth Bockes looked much like these examples: small, monochrome or sparsely coloured, and tightly focused on a single, emotionally charged motif.

For the purposes of this blog post, however, the precise iconography matters less than the interplay between verbal description and visual prompt. The letters do not merely note that a Christ Child in a heart has been sent. They supply its Passion background (opened with the sharp spear), spell out its emotional effect (honey-sweetness, consolation), and sketch its eschatological horizon (a snow-white soul resting in the wound). The image, in turn, offers the recipient a fixed visual form through which to re-run that script in daily devotion. Text and image, in other words, function as a single devotional package—what we might, borrowing the language of media theory, call a co-authored interface between divine grace and human perception.

“The Fairest Jewel I Know”: Christ as New Year’s Treasure

The New Year’s wishes go far beyond a mere exchange of greetings. They script the gaze and help foster a shared devotional culture between convents, regardless of enclosure. In another New Year’s Eve letter (letter no. 254), a younger nun at Lüne writes to Elisabeth Bockes again, this time thanking her not only for practical support but also for an exhortation, a spiritual letter from which she has drawn sweetness as a child receives scented roses from its mother. Her heart, she says, has been refreshed thereby.

She then recalls Gregory the Great’s saying that true love proves itself in works and admits she can only partly live up to this ideal. Even so, she resolves to send Elisabeth what she calls the fairest jewel she knows:

Hirumme, karissima Elisabeth Bockesken, so sende ik juk in rechter leve dat aldersconeste, suverkeste, begherlikeste klenade, dat ik wed in hemmel unde in erde, unde dat is Jesus Christus, dat sote kyndeken…

Therefore, dearest Elisabeth Bockes, I send you in true love the fairest, purest, most desirable jewel that I know in heaven and on earth, and that is Jesus Christ, the sweet little child.

The “jewel” is again a devotional image of the Christ Child on a small sheet of parchment, likely similar to the one described in the earlier letter. What matters most is not its artistic sophistication (these images are often described in the letters as little, even crudely painted) but the value conferred on it by language. Strings of superlatives—most beautiful, most pure, most desirable—elevate an inexpensive, fragile object into a jewel worthy of a beloved friend. The New Year’s image becomes a crystallization of affection, of remembered reform, and of the desire to send something that can bridge distance in both space and prayer.

A Golden Heart and a Snow-White Soul

Another New Year’s letter (letter no. 261), written in the characteristic code-mixing language of the nuns, switching between Low German and Latin, to the younger sister of the sender, a nun in Ebstorf, sends yet another Christ Child in a heart, this time explicitly at the beginning of this new year:

Et in amore eiusdem piissimi salvatoris ac sponsi nostri dirigo vobis illum immensum magnificum regem universe terre quasi parvulum infantulumdepictum in aureo corde ad initium istius novi anni,

And in love for the same most merciful Saviour and our Bridegroom, I send you, for the beginning of this new year, that immense and magnificent king of the whole earth portrayed as a small, tender little child in a gold heart…

Here the heart is golden, and the metaphor unfolds accordingly. By the “sweetness of his honey-flowing humanity, the Child is to gild the addressee with love, both in soul and in body, inwardly and outwardly, so that she may begin the new year renewed in mind and spirit: good, health-giving, prosperous, and peaceful. The writer presses the image further. She hopes her sister will be bound so closely to Christ’s heart in contemplation that she can never be separated from him; that in her final hour her soul will fly, snow-white, through Christ’s side-wound into the golden nest of his heart; and that the bitterness of present death will be transformed into sweetness.

In this short passage, New Year, heart, marriage, death, and resurrection are all folded together. The heart emerges at once as a place of dwelling, a nest for the soul; as a womb or bridal chamber, the intimate space of union between Bridegroom and bride; as a treasury, golden and honey-flowing, a source of gifts for body and soul; and as an anatomical detail grounded in Passion piety, opened by the spear and reached through the side wound. If we think of the intellectual history of the Sacred Heart as beginning with twelfth-century Cistercian and Victorine writers and crystallizing later in early modern French devotion, these Lüne letters reveal a late medieval northern German iteration that is both strikingly visual and strikingly seasonal: the heart as a New Year’s image, carefully painted on a small leaf and mailed across the Lüneburg Heath region.

Hearts as Media of Devotion

What, then, does all this offer to intellectual historians?

These letters first remind us that ideas about the heart, its anatomy, its affective charge, its role in salvation, were not confined to theological treatises. They circulated through small objects, stock phrases, and seasonal rituals. The Lüne writers draw on a shared reservoir of imagery: the opened heart of Christ from twelfth-century mystical theology, the bridal language of Christ as sponsus, the long medieval fascination with Christ’s wounds as entrances to safety and sites of empathy. Yet they recombine these motifs in strikingly specific ways. By tying the heart to the New Year, they turn it into a temporal device, a means of beginning again; by placing the Christ Child within the heart, they fuse Incarnation and Passion in a single image; and by imagining the heart as a golden nest for the soul, they figure the afterlife in profoundly domestic, almost cozy terms.

Second, the letters show how visual and verbal media work together to shape devotion. The images would have been almost meaningless without the accompanying “scripts”: letters that tell the beholder when to look, which body parts to imagine, which biblical stories to recall, and what effects to desire—health, joy, perseverance, a blessed death. Conversely, the letters gain much of their force from the promise of a tangible object. Without a devotional image, a New Year’s greeting remains a courteous text; with one, it becomes a kind of portable altar, a miniature interface between the recipient’s daily life and the mysteries of Christ’s humanity.

Finally, these materials complicate any simple story about enclosure and isolation. The very existence of such rich New Year’s correspondence, replete with gifts, shared images, and carefully crafted devotional language, shows that women’s convents like Lüne and Ebstorf were embedded in dense networks of exchange: textual, material, and emotional. Reform did not close these channels; it reorganized them. not close these channels; it reorganized them.