By Adrastos Omissi

Byzantium is, for most, a rather dirty word, connoting something faintly alien and somehow obscene. To classicists, the Rome that did not fall is an embarrassing pantomime horse, cavorting about in the ill-fitting clothing of the once great Roman Empire. To medievalists, it is an outsider, a distinctly foreign looking entity lingering on the edges of a Europe to which it does not belong. It is Greek, it is lurid, it is decadent. Above all, it is irrelevant.

Historians of Byzantium recognise these viewpoints as erroneous, but I fear they still have much work to do in getting the word out. The prejudices of our own disciplines (note that those who study the medieval world are medievalists, unless they happen to study Byzantium, in which case they become byzantinists) have a tendency to lock us away from recognising the enormous influence that this supposedly alien power had upon many of the social and intellectual stories that we consider to be so distinctly Western. No more so is this true than of the so-called renaissance in Italian art that took place in the period roughly bounded by the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries.

It may seem that the art of the Byzantine East – static, golden, otherworldly – has little indeed to do with the vitality, the realism, and the sheer ambition of Italy – and Europe’s – renaissance, that explosion of creative energy that seemed to blossom, unbidden, in the Latin speaking West after the thirteenth century. Cursory familiarity with Byzantine art confirms this and indeed confirms the opinion of Giorgio Vasari, the Italian painter turned historian, whose 1550 Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, from Cimabue to Our Times essentially defined the renaissance – the rinascita – as a rejection of ‘that clumsy Greek style’ (quella greca goffa maniera) and the creation of a new naturalism that captured the human form in ways not known before. But it may be that the art historian doth protest too much; Vasari’s very emphasis on the ways in which the artists of his own day had surpassed the Greek models indicates just how deep was Byzantine influence on Italy’s artistic culture.

One of the bright lights of Vasari’s renaissance, the man he saw as truly kick-starting the turn towards naturalism, towards capturing authentic human emotion, and towards tricks of composition like perspective, was Giotto. Giotto, a Florentine artist who lived between 1267 and 1337, was an archetype of true artistic genius, a former shepherd whose prodigious talent was unlocked when the artist Cimabue discovered him sketching his sheep with a pointed rock. The sheer life and expression of Giotto’s paintings instantly strike the observer and – unlike his teacher Cimabue – seem to have nothing at all in common with the frozen, abstract forms of the East.

But uniquely gifted though Giotto surely was, his art and the movement it inspired owed more to Byzantine influence than we might at first believe. At times, these debts can be seen almost directly. In the tiny mountain village of Gorno Nerezi in modern day Macedonia lies the externally unremarkable late Byzantine church of St Panteleimon, patronised by the imperial family and decorated inside with a fresco cycle completed by artists from Constantinople. These frescoes, completed at some time in the twelfth century, burst with energy and an emotional intensity that might surprise viewers accustomed to think of Byzantine art as frozen and lifeless. The frescoes are crowded with varied figures and with a sense of movement and action. Each face tells a story in its expression, no more so than the tortured, wailing face of Mary, the Mother of God, who holds the body of her dead son, taken down from the cross. The artist has made this divine moment painfully human. Though Giotto himself surely never saw this image, the comparison with his own Pietà is so striking as challenge any notion of coincidence and, indeed, to challenge the notion that Giotto and his like had done something unprecedented in seeking to capture the intensity of human experience in the look of a face or the shape of a body. Giotto’s models, like those of St Panteleimon, were firmly Byzantine, and it was by working and experimenting with techniques from the Greek East that Giotto’s own remarkable paintings were produced. Without Byzantine art, Giotto might have remained on his hillside, drawing sheep in the dirt.

That the Italian masters whose work began the renaissance should have been inspired and indeed trained by Byzantine artists and models is hardly surprising. Byzantine art had long exercised enormous influence in the Italian peninsula, not least because it was not until 1071 that the Byzantines finally lost their last territories in Italy. Throughout the period of late antiquity and the middle ages, evidence – both direct and indirect – of Byzantine artists at work within Italy can be found and Byzantines were clearly often seen as masters to be copied.

Direct evidence of their work can take the most striking forms. Within the tiny church of Santa Maria foris portas in Castelseprio in northern Italy, long hidden under plaster, is a cycle of late eighth or early ninth century Byzantine frescoes, which, like those at Panteleimon, defy the stereotypes of Byzantine composition and are among some of the most remarkable early medieval frescoes ever to be discovered in the Latin West. The depicted image shows the Annunciation, in whose frame the movement of the archangel Gabriel, swooping down to announce the Good News to the supine and unsuspecting Mary, is boldly evoked and the folds and contours of the clothing that covers the two figures betray the living bodies beneath the cloth. The composition eschews the linearity and the stasis that we are told to expect from eastern art. Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, the Castelseprio frescoes demonstrate both the vitality of the Byzantine artistic tradition and its deep influence within Italy.

Castelseprio is merely one of dozens if not hundreds of specific examples that may be adduced to show the activities of Byzantine artists at work in Italy. Another spectacular example of such – and at the opposite end of the spectrum from Caselsprio in terms of its sheer monumental grandeur – is the great church of San Marco in Venice. Built at the end of the eleventh century to a Greek cross plan and with Byzantine expertise, the church is surmounted by five enormous domes that float upon pendentives above the Venetian lagoon and was constructed as a conscious model of Constantinople’s now lost Church of the Holy Apostles. Its interior still gleams with a cascade of Byzantine-inspired gold mosaic work. Even the ardently anti-Byzantine Vasari admitted that the first great master of his Lives, Cimabue (c. 1240-1302), learnt to paint by bunking off from his studies to watch at work the Byzantine painters who had been summoned to Florence ‘for no other reason than to restore the art of painting, which had long since been lost in Tuscany.’

A certain sense of superiority in comparing Italian art to that of the (fallen) Byzantine Empire was easy for renaissance Italians to project back into the past, standing upon the self-confident vantage point of centuries of innovation, but to do so today ignores the enormous influence of outsiders upon Italy, Byzantium at their forefront. The adaptations of Byzantine models produced some of Italy’s most spectacular art and architecture. The commissioning of the so-called Gates of Paradise by Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1401, a masterpiece of bronze relief sculpture still to be seen on Florence’s Battistero di San Giovanni, has sometimes been taken to mark the starting point of Italy’s renaissance, but in the centuries that preceded Ghiberti it was the foundries of Constantinople that produced Italy’s finest bronze doors, as at Sant’Andrea in Amalfi, at the abbey church of Monte Cassino, at San Paolo fuori le Mura in Rome, at San Sebastiano in Atrani, at the Cathedral of Salerno, and more besides. Like Giotto and his suffering Mary, these influences ran deep and ‘renaissance’ amounted to a reinvention of inherited models, not a rejection of them.

None of this, of course, is an attempt to deny the brilliance of the Italian renaissance, an explosion of creativity that brought into being some of the greatest works of art the world had ever seen. Yet seen from a western perspective, it is important to recognise that these are not merely rungs on the ladder of Western genius but part of the story of an interconnected world, a world in which, for many centuries until its fall, Byzantium (not to mention the Arab world) set the pace of cultural change. Medieval scholars need to train themselves to look for these interconnectivities and to remember that Western authors have always, since the days of Charlemagne, sought so hard to paint the Byzantine Empire as the irrelevant vestige of a once great power precisely because Byzantium’s influence stretched so far and reached so deep.

Picture captions:

- Picture 1: Golden and glorious: Christ Pantocrator from Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (late 13th century).

- Picture 2: Giotto’s Pietà in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, one of the artist’s great masterpieces (completed 1305).

- Picture 3: The Lamentation of Christ as depicted in the St Panteleimon fresco cycle (mid-12th century).

- Picture 4: The Annunciation from Castelseprio (late eighth / early ninth century).

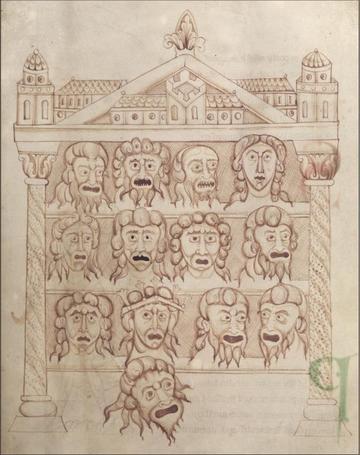

- Picture 5: The genius of Byzantine relief sculpture: the Harbaville Triptych, an example of the vibrant and flourishing artistic culture under the Macedonian dynasty, 867-1057.

– Adrastos Omissi, British Academy PDF