“OH, I’ve had such a curious dream!” said Alice […]

– Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll)

Going back to Germany after my two-week adventure in Oxford, I, just like Alice, felt as if waking up from a magical dream. It is not an overstatement to say that the city has bewitched me and, trust me, you don’t have to be a huge Harry Potter geek (which I nevertheless am) to fall under its spell. No wonder the city served as inspiration for Lewis Carroll‘s most famous novel. Instead of a White Rabbit with a big pocket watch, it was Henrike Lähnemann with her trumpet whose call I followed. Prof. Lähnemann kindly invited me to the XML summer school taking place yearly at St Edmund Hall and to spend another week as her intern at the Sommerakademie of the German Scholarship Foundation

“Treacle Well“ in Alice in Wonderland

“CURIOUSER and curiouser!”

– Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll)

There‘s no better way to describe my time in Oxford. From the start, the theme of my visit was “Looking behind closed doors“. I arrived just in time for the Oxford Open Doors, which take place each year in September and allow the public a sneak peek into Oxford’s Colleges. For me that meant: see as much as you can within one day! I think I almost walked 40 000 steps that day, but the visual enrichment made more than up for the physical fatigue.

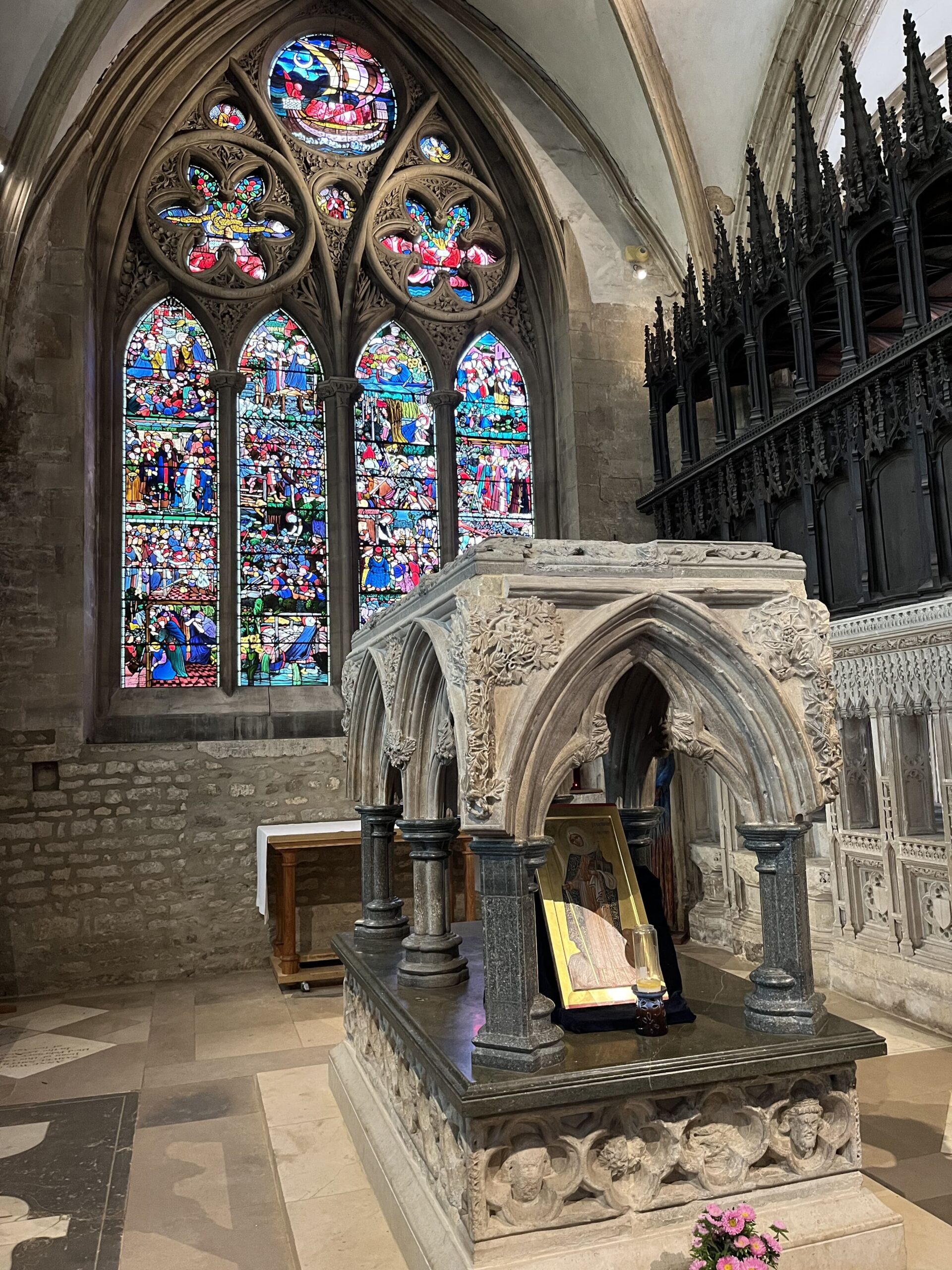

While, outside of Open Doors, you can get into some colleges by simply asking nicely or pretending to be a prospective student, you usually need to pay an entrance fee, which can vary from £2 to up to £20, depending on the colleges prestige and their Harry Potter screen-time. The best way to get inside without having to pay is to go to a college chapel service or evensong. No one can fine you for wanting to go to church and no one will come after you if you walk the grounds a little afterwards. (As long as you don’t step on the grass!) Prof. Lähnemann took us to Christ Church Cathedral on the first day of the Sommerakademie, where we were able to enjoy all the pomp and circumstance of an Anglican church service and the angelic voices of Christ Church’s choir.

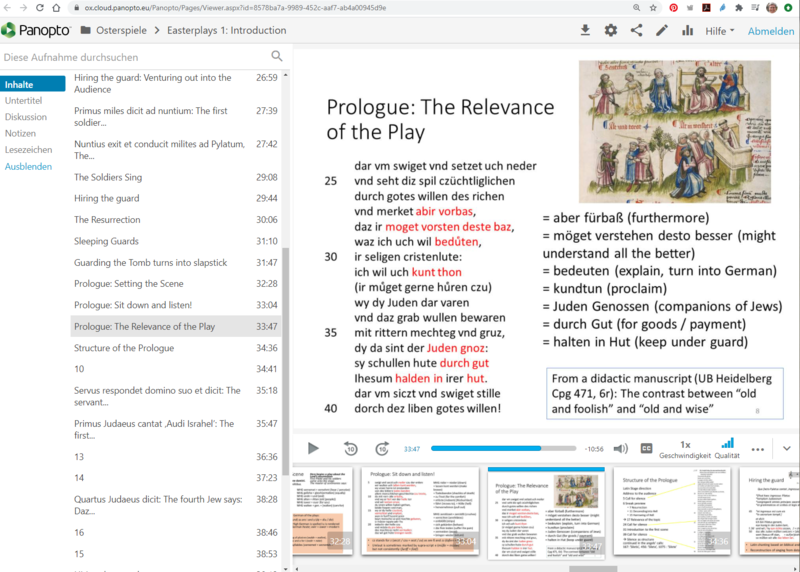

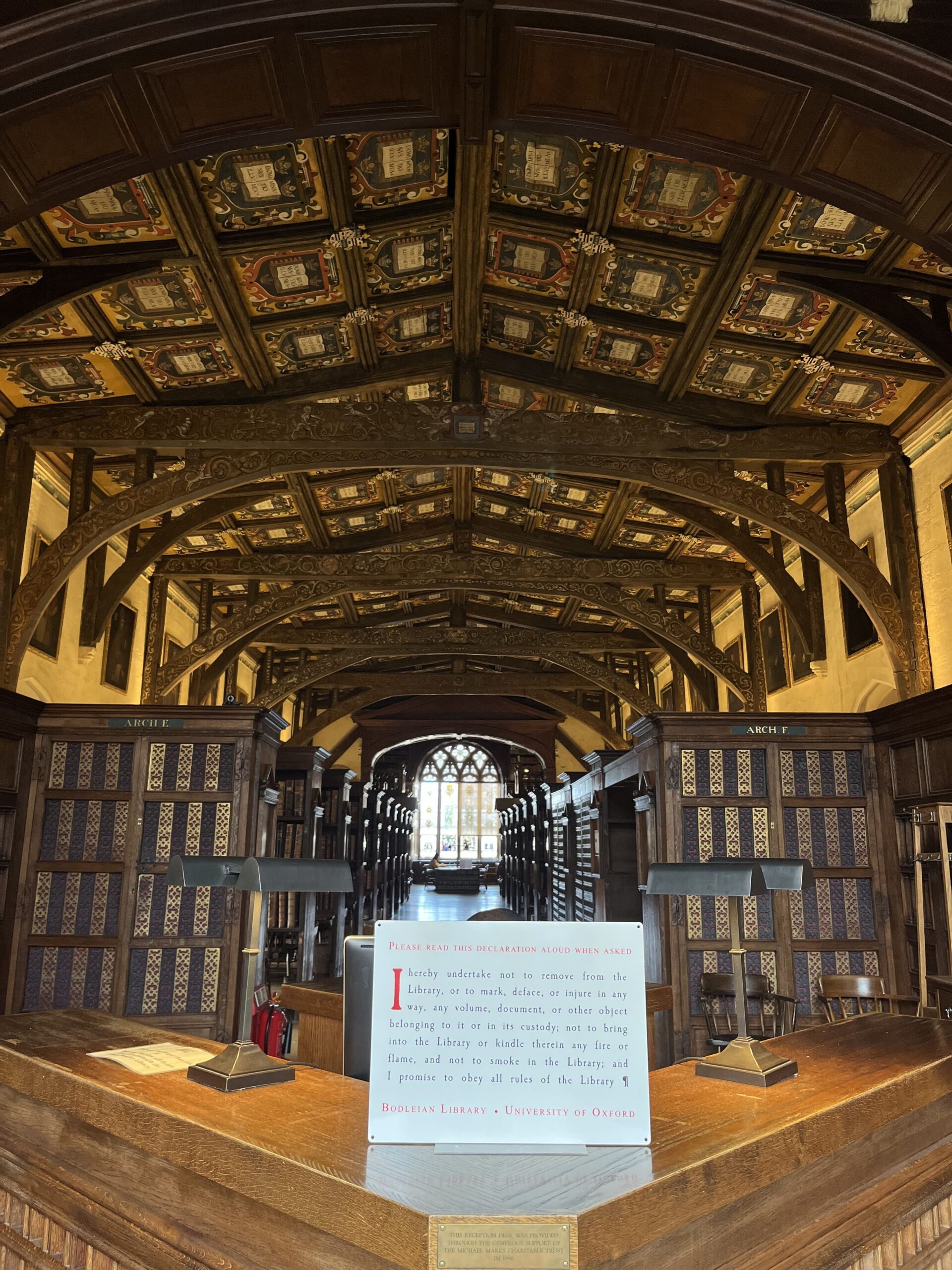

As the saying goes “When one door closes, another one opens up“, I spent my second week as part of Prof. Lähnemann’s working group “Opening the Archives“. The object was to create a digital edition of Martin Luther’s pamphlet “Wider die mörderischen und räuberischen Rotten der Bauern“ (1525), which is going to be published in November 2025 in the Reformation Series of the Taylor Editions. Together with her colleague Dr Andrew Dunning, Prof. Lähnemann gave us enlightening insights into the history of bookmaking, the collection of Reformation pamphlets in Oxford, and printing practices in the 16th century. We even dabbled a little in some printing work ourselves at the printing workshop of the Bodleian Library.

At the end of the week, we had not only gained a better understanding of the Reformation and the Peasant’s War, but, thanks to Emma Huber, the German subject librarian and DH lead at the Taylor Institution Library, also made our own transcription and edition as well as curated an exhibition case at the Taylorian.

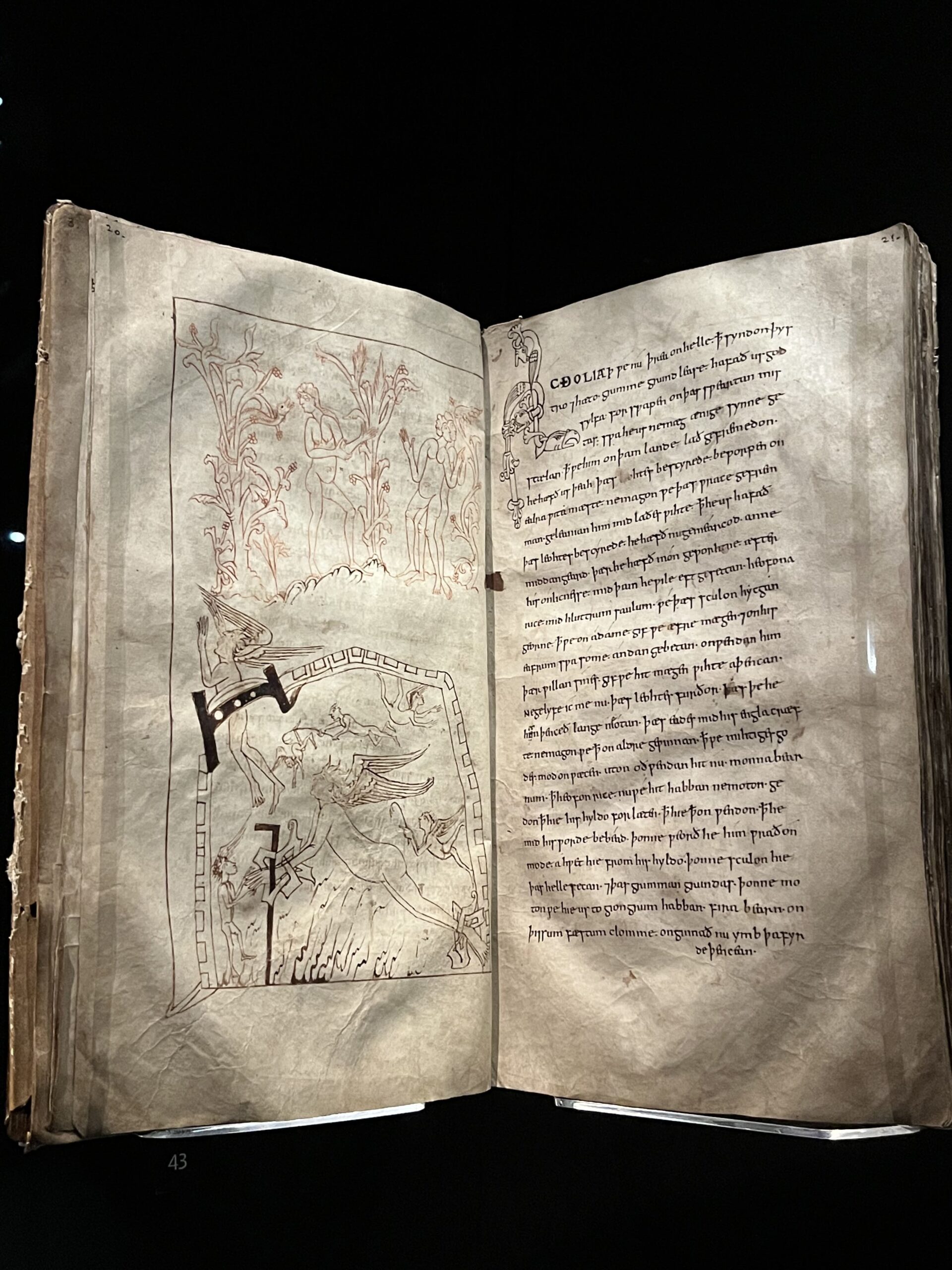

One of the key lessons I learned during my time in Oxford is to approach all objects with curiosity and to look closely. There is usually a story behind the smallest and most insignificant-seeming thing – whether it be an old shoe scraper or an inconspicuous pencil marking in a book. Our little group was lucky enough to have access to those parts of the University not open to the public, but many of Oxford’s treasures are not kept under lock and key. The “Treasured“ Exhibition at the Weston Library is a great example of that. Free of charge, you can gaze at various precious specimens of the Library’s collection.

But you don‘t even always need to step inside to discover hidden treasures. Simply by walking through Oxford’s streets with attentive eyes, you‘ll see things that seem to come straight from Wonderland: Gargoyles staring down at you in no way less grotesque than Carroll’s grinning cat; or the beak heads around the entrance of St Peter-in-the-East (St Edmund Hall) and St Mary’s in Iffley, which are – to put it once more in Carroll’s words – “indeed a queer-looking party“.

A Mad Tea Party

As Alice learns during her Adventures, it often is not so much about what you do, but who you do it with. It makes a huge difference if you have a tea party with a mad hatter, a March Hare, and a dormouse or with your old aunt Agatha. It’s the people that make an event unforgettable. And that summarizes my summer school experience(s) quite nicely. Especially during the first week at the XML summer school, where I, as a medieval Germanist and foreigner to the digital world, only understood about 30% of what was being taught. However, I met so many fascinating, inspiring people and had interesting discussions, in which new perspectives opened up to me. The same holds for the Sommerakademie of the German Scholarship Foundation: Young people from all different subjects and backgrounds coming together, sharing ideas, knowledge and always a good laugh. That is why I regard tea breaks, lunches and dinners as an essential part of the summer school experience. They give you the chance to connect with other people, socialise, pick up interesting conversations, and, of course, enjoy the excellent food! (In that respect Teddy Hall excelled. But you need to be quick when it comes to pudding, otherwise you might face an empty tray and ask yourself: “WHO stole the tarts?“) Staying on the topic of food and socializing, I would advise everyone to visit the Coffee Mornings at the Weston every Friday at 11:30 am. Alongside tea, coffee and biscuits there is a talk on a different topic every week, so no matter which subject you are coming from, there will be something for you. It is a great opportunity to see some of the unique holdings of Oxford’s libraries and gain an insight into current research projects at the university.

I want to take this opportunity to thank the person who most prominently shaped my Oxford experience: Henrike Lähnemann. One thing is for sure, had I been interning for another Professor, the two weeks would have been less crazy, lacked fun, less memorable. So next time you think you hear the distant call of a trumpet, follow it! It might lead you into Wonderland…

Judith Habenicht is a German and History student at the University in Heidelberg who spent two weeks in Oxford on a placement with Henrike Lähnemann