During the Medievalist Coffee Morning on Friday, 21 June 2024, Henrike Lähnemann launched her new book The Life of Nuns. Love, Politics, and Religion in Medieval German Convents, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers 2024, open access: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0397

To purchase a paper copy with a 20% discount, use the code LONHL_24 at checkout

On show were the following five manuscripts, all available digitised via https://medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/, three from the Cistercian convent of Medingen near Lüneburg (http://medingen.seh.ox.ac.uk/) and two Rules for female convents:

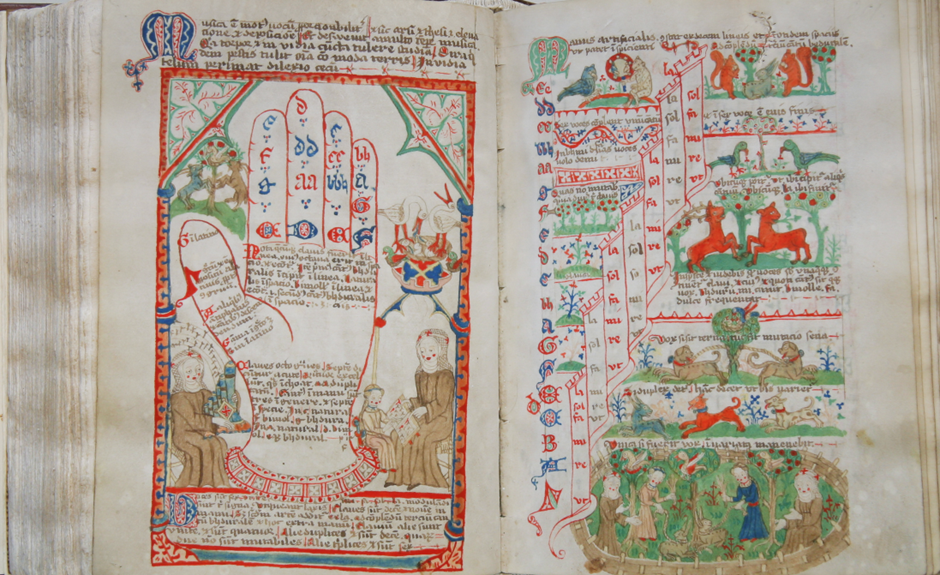

- Medingen O1: Bodleian Library, MS. Lat. liturg. f. 4: Prayer book: Easter (end 15th to early 16th cent.), fol. 174v: the community of nuns; fol. 288r: Music notation

- Medingen O2: Bodleian Library, MS. Lat. liturg. e. 18: Manual for the Medingen Provost (1472/1479), fol. 36v/37r: liturgical drawings; fol. 47vb: Harrowing of Hell initial

- Medingen O4: Bodleian Library, MS. Don. e. 248: Psalter by Margarete Hopes (early 16th cent.), fol. 173r: Harrowing of Hell; fol. 196r: Resurrection

- Rule of St Augustine https://editions.mml.ox.ac.uk/editions/rule-of-st-augustine/: Bodleian Library, MS. Germ. e. 5 (c. 1395)

- Rule of St Clare: Bodleian Library, MS. Lyell 68, 1457

Following this, there was a presentation by Stacie Vos (Ann Ball Bodley Visiting Fellow in Women’s History) talk about Women doing medieval studies in the early 20th century. Stacie reflected on the legacies of several early-20th-century women medievalists who pursued academic and extra-academic careers. She started the group ‘Enclosure’ which January 2021 to February 2024 was hosted at the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages under enclosure.mml.ox.ac.uk, now archived at the Bodleian Library Web Archive.

***

It all started with a mistake: ‘Der Spiegel’, a widely read news magazine in Germany, ran a double-spread article on the big research project which Eva Schlotheuber and I direct, the edition of 1.200 letters from the Benedictine convent Lüne in North Germany. In the interview for it, we had talked about how important education by the nuns was for the ‘Lehrkinder’, children educated at the convent. The girls would come into the community, aged 7 to 9, and then get a thorough grounding in a wide range of discipline such as music, as pictured in the scene from a text book from Kloster Ebstorf.

Der Spiegel’ turned our phrase of ‘Lehrkinder’ into ‘die Kinder der Nonnen’ (the children of the nuns) – hinting at sex and scandal behind convent walls (in 2/2020 ‘So colourful was the life of nuns in the Middle Ages’).

This sparked further media interest and the Ullstein publishing house approached us because it had piqued their interest. When we explained that the attention-grabbing headline about “the nuns had children” was based on a misunderstanding, they were slightly disappointed – but then offered us the opportunity to set the record straight. And, arguably, what we could offer was much more exciting: the colourful and detailed accounts of lively, intellectual, strategic, argumentative, powerful women, shaping religion and politics of their times, looking after the girls (despite or even because they were their spiritual and not biological daughters!), negotiating business deals, writing, painting, composing and influencing the way we live today through their books, songs, and art.

‘The Life of Nuns’ tries to capture the richness of the life of these medieval nuns by incorporating as much primary source material as possible. Each of the big topics – such as Education, Music, and yes: Love and Friendship – starts with an account taken from the diary of a nun who lived at the end of the 15th century in the convent St Crucis in Braunschweig. The anonymous author covers the high feasts – celebrating the entry of new nuns, welcoming illustrious visitors – and the everyday mundane events – lice, Lebkuchen (gingerbread), laundry. And we end every of our chapters with the presentation of a significant art work from the convents: the impressive wall paintings done in the 14th century by “three nuns all called Gertrud” in Wienhausen, the largest medieval world map in Ebstorf (30 goatskins sewn together), tapestries, statues, stained glass, the oldest spectacles in the world (fallen through the floorboard cracks in the nuns’ choir) – an embarrassment of riches from a world that few people even know existed. That is particularly true for an Anglophone audience since so much of the evidence is lost due mainly to the dissolution of the monasteries but also a repurposing of surviving architecture and treasures. Compare Kloster Wienhausen and Godstow Abbey: in Wienhausen we have got the full set of monastic buildings, cloisters, huge grain stores, cells, corridors, imposing Gothic nuns choir and more – and everything that furnished it: stained glass, wall paintings, sculptures, down to the different set of dresses for the statues.

In Godstow, on the other hand, we can sense the dimensions of its former power by looking at the impressively long surrounding wall of enclosure and glimpse some of its stylish beauty from the ruined chapel at the back – the rest is only possible to reconstruct from scant archival evidence. Looking at the German counterparts, who shapeshifted through the Reformation, transforming into Protestant female communities who still look after the rich tapestry of medieval life, offers the chance to rectify this in part – and encounter the Life of Nuns at their fullest, mystical, worldly, polyphonous and very much relevant still today.