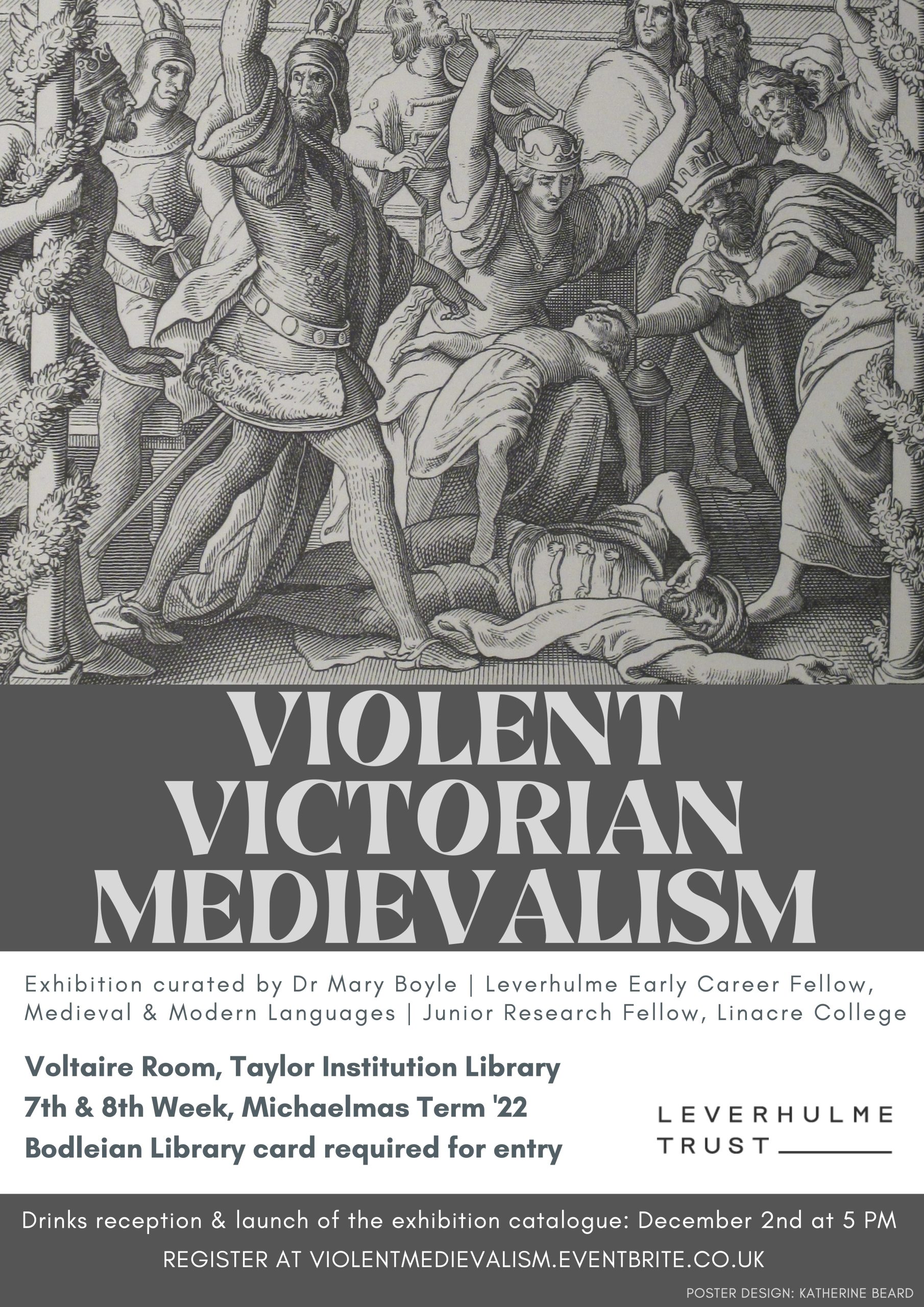

Taylor Institution Library, 21st Nov-2 Dec 2022 and online

medievalism, n.

‘the reception, interpretation or recreation of the European Middle Ages in post-medieval cultures’

‘Violent Victorian Medievalism’ is an exhibition taking place at the Taylor Institution Library (21st November-2nd December 2022) and online. It tells part of the story of how ‘medieval’ often becomes synonymous with ‘violent’ in later responses to the Middle Ages by bringing together some of the Bodleian’s collection of Victorian and Edwardian English-language adaptations of the Nibelungenlied and related material. These publications are accompanied by eye-catching images, often focusing on some of the more violent aspects of the narrative.

The Nibelungenlied is the most famous medieval German version of a collection of heroic legends known also in various Scandinavian incarnations. It tells of the hero Siegfried, his courtship of the Burgundian princess, Kriemhild, and his involvement in facilitating the marriage between Kriemhild’s brother, King Gunther, and the warrior queen, Brünhild. Siegfried is subsequently betrayed and murdered by Gunther and Hagen, the king’s vassal. The widowed Kriemhild subsequently marries Etzel, King of the Huns, and engineers a catastrophic revenge, resulting in the complete annihilation of the Burgundian men.

Rediscovered in the eighteenth century, the Nibelungenlied was quickly acclaimed the German national epic, but over the course of the nineteenth century, various anglophone writers also identified it as their own cultural inheritance, based on a belief in a shared so-called Germanic ancestry. Particularly after the premiere of Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen, English-language adaptations proliferated, often illustrated, and many aimed at children. While – given the Nibelungenlied’s plot – references to violence are unavoidable in adaptations, it is striking how often editors or adapters chose to highlight these events in illustration.

Panels

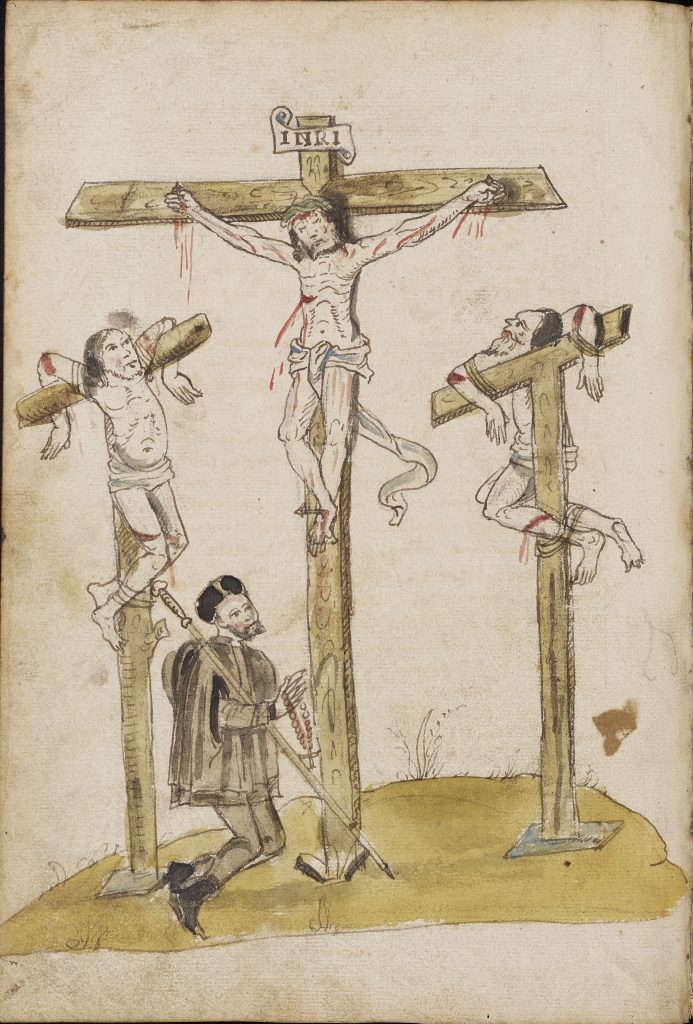

Here we see heroes who will not go on to triumph, whether they are to meet their deaths in a blaze of glory, or as a result of betrayal. Two images show Hagen’s cowardly murder of the great hero, Siegfried, whose strength and invulnerability mean that he can only be destroyed through deception. One image shows Hagen’s desperate and violent attempt to disprove a dreadful prophecy that all but one of the Burgundians are doomed, should they continue with their journey. The other images depict the Burgundian warriors, fighting unrelentingly in the face of certain death. This panel shows courage and pathos, bravery and treachery, and it tells a complex tale: Hagen is the aggressor in several of the images, yet one of the valiant warriors fighting against the odds in the others.

The Nibelungenlied was viewed as the German national epic, but anglophone writers often also staked their own claims to it. The underdog’s struggle against immeasurable odds is a frequent feature of national narratives, including in this country, and we see here warriors depicted at their defining moment, characterised not necessarily by their virtues or achievements, but by their most desperate experiences.

The chief architect of much of the violence in the Nibelungenlied is the beautiful Queen Kriemhild, seeking revenge for Siegfried’s death. This was a source of difficulty for many nineteenth-century adapters, who sought variously to make an example of her, to make excuses for her, or to rehabilitate her entirely. But even where there was an attempt to explain her actions, the temptation to depict her at her most transgressive – brandishing the decapitated head of her brother – was almost irresistible. And the scale of that transgression also gave illustrators licence to depict Kriemhild’s own violent death, with her final victim, Hagen, lying at her feet.

Kriemhild is not the only violent woman in the Nibelungen material. Her sister-in-law, Brünhild, who is a valkyrie in both Norse legend and Wagner’s Ring, was possessed of immense physical strength before her marriage, and children’s books in particular often include images of her with her spear. In contrast to Kriemhild, there is ultimately no direct victim of Brünhild’s violence, but the illustrators commonly show the fear of the male heroes, as they cower behind a shield, emphasising the threat offered by a physically strong woman.

In this panel, we see the continuities between nineteenth-century medievalism and more recent medievalist fantasy material, particularly onscreen (e.g. Game of Thrones, The Hobbit, Merlin, Harry Potter). Siegfried’s fight with the dragon takes place entirely off-stage in the Nibelungenlied, and it is only mentioned once or twice in passing. It is, though, far more prominent in other traditions, and its appeal to illustrators, especially of children’s adaptations, needs no explanation.

These versions for younger readers frequently avoid adapting, or fully adapting, the second half of the narrative, with its focus on brutal vengeance. This has the effect of rebalancing the story into one focused entirely on Siegfried’s heroics, with Kriemhild simply functioning as a mild and beautiful love interest. Such adaptations also tend to bring in material which is omitted from, or played down in, the Nibelungenlied itself. While Siegfried’s violent death prevents such adaptations from culminating in a traditionally child-friendly happy ending, their emphasis on fantasy elements like the dragon give them a fairy-tale quality which we recognise today.

Sign up for the closing reception

Mary Boyle, November 2022