This post serves as a dual introduction, both to Arnold von Harff and to late-medieval pilgrimage writing more broadly. The latter goal in particular is, admittedly, rather brave.

Who was Arnold von Harff?

This is a question which Harff wants his audience to answer in a particular way. As he never tires of reminding us, he was a knight from an aristocratic family. To be more specific, he was the middle son of a nobleman, Adam von Harff. He was born around 1471 at the family seat of Schloss Harff in Bedburg, a castle which was demolished in 1972 for the sake of opencast brown coal mining, along with the whole associated settlement (to see full-size versions of any images, click through twice).

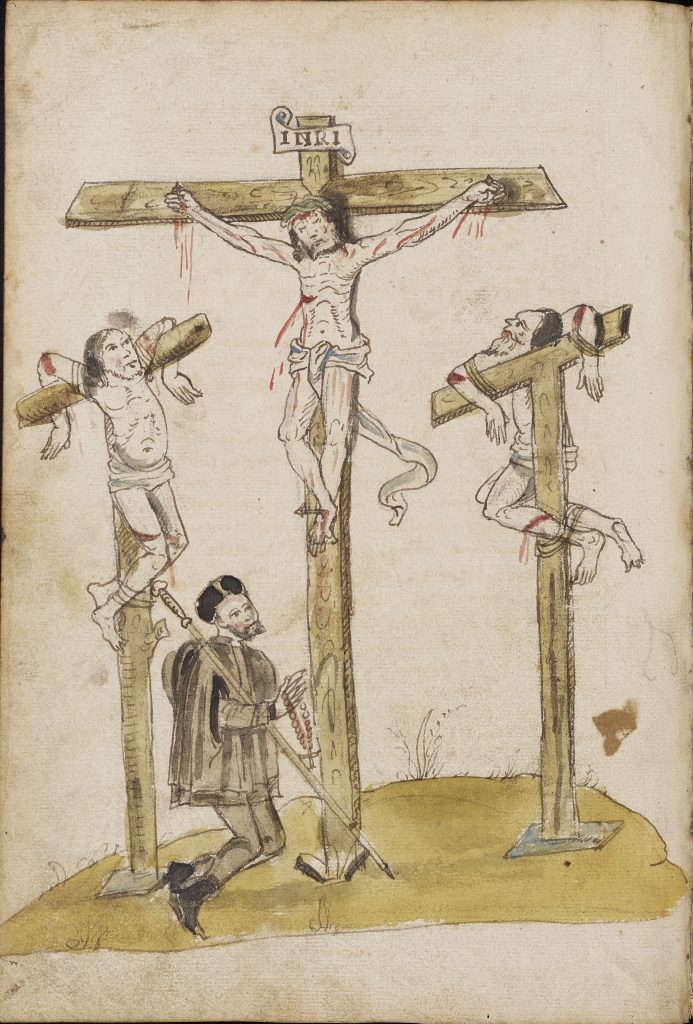

As you can see, pretty much nothing survived, but the Crucifixion group which had been in the churchyard since 1531 was moved to the new settlement and affixed to the modern church wall. It bears some striking similarities to the Crucifixion image transmitted with Harff’s Reisebericht, the earliest version of which is roughly thirty years older than the group (though note that this version of the image, as transmitted in MS Bodl. 972, post-dates the statues by about twenty years).

Harff set out from Cologne at the age of twenty-five on a rather ambitious programme of pilgrimage: he apparently planned as highlights Rome, Sinai, Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostela, St Patrick’s Purgatory on Lough Derg, and Wilsnack. He did reach the first four of these destinations. He also, apparently, made it to many further-flung locations, some of them evidently only by travelling on the page. As previous generations of scholars have observed, a fair amount is clearly carried over from other sources including, but not limited to, Marco Polo, Odoric of Pordenone, Ptolemy’s Geography, and – perhaps most significantly – John Mandeville’s Book, also known as Mandeville’s Travels. In any case, Harff didn’t make it to Wilsnack or Ireland. He returned home in 1499. In 1504, he married Margarethe von dem Bongart and followed his uncle in the post of hereditary chamberlain at the court of Guelders. His story has a rather sad ending: he died only a year later, in 1505, leaving his wife pregnant. Their daughter died too, in early childhood, and was buried with him. But his writing has survived, and was fairly popular amongst members of his own social class in the Rhineland and Westphalia. It continued to be circulated in manuscript into the seventeenth century, though it was not printed until 1860. It was then edited by Eberhard von Groote, using three manuscripts in the Harff family archives, including one that, while unlikely to be an autograph, dates from shortly after Harff’s journey.

What is late-medieval pilgrimage writing?

So let’s now turn to the Reisebericht’s literary context. The first thing to do here is to separate the practice of actually going on a journey from the accounts of travel that we find on the page, even if they are written by people who really have travelled. It’s a constant refrain today that the lives people recount on social media are not identical with the lives they’re actually living: social media offers us the curated version, often carefully groomed to leave certain details out or to foreground others. It’s – usually – a version of reality, based, at least to an extent, in what has actually happened, but it doesn’t quite overlap. I don’t simply mean this in the sense that recounting exactly what happened at every moment of every day would be both tedious and impossible, or even particularly that people’s memories are flawed and subjective, though of course that’s true. It’s the gap between the picture of a historic landmark apparently on its own, while in reality, locals waited impatiently behind the photographer, who was carefully adjusting the angle to avoid the crane behind it and the modern building in front of it. A fifteenth-century pilgrimage on the page and a fifteenth-century pilgrimage as it really happened are deliberately and consciously different, and when we read pilgrimage writing, we’re looking at journeys on the page. Despite the huge range of texts which come under the heading of ‘pilgrimage writing’, and the scope for variation beyond descriptions of the pilgrimage site themselves, there are conventions which, certainly by the time Arnold von Harff was travelling and writing, are quite rigid when it comes to recounting visits to the Holy Places in Jerusalem.

So let’s focus in on Jerusalem. One of the key factors behind this conformity was the Franciscan Order, who had been granted the Custody of the Holy Land in 1342 by Pope Clement VI. The pilgrimage programme the Franciscans developed endured with little variation for two centuries. The sites to be visited, the liturgy at each, the order in which they were seen, the route between them, and the terms in which they were described, were shared by late-medieval western pilgrims making the Jerusalem pilgrimage (though parts of the route could be taken in reverse). But the Franciscans weren’t content for their programme to remain in Jerusalem. Pilgrims brought it back with them in their accounts, and the pilgrimage was so formalised that pilgrim authors frequently copied one another’s words, and the advent of print in the second half of the fifteenth century really speeded up this process.

Although Harff’s account wasn’t itself printed, he made use of printed accounts in his writing process, including the Peregrinatio in terram sanctam of one of the Big Names of German pilgrimage writing: Bernhard von Breydenbach. We can see traces of this rather mammoth work in text and image in Harff’s account. His section on Greek Christians is a key example, and several alphabets are also lifted from Breydenbach. Nonetheless, most of the images transmitted with Harff’s Reisebericht cannot be traced to Breydenbach.

Another crucial source for Harff (and for many others), and almost certainly another printed one, is John Mandeville’s Book. This is purportedly the first-person description of an English knight’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land and his further travels in the East. It appeared in French in the second half of the fourteenth century, was transmitted widely in manuscript, and rapidly translated into various vernaculars including, by 1415, two separate German translations, those of Otto von Diemeringen and Michael Velser. Both were printed in 1480. Mandeville’s depiction of the Holy Land was enormously influential – despite the fact that it was also long out of date by the time of its first appearance, being largely dependent on crusader-era sources, and without reference to the Franciscan pilgrimage.

The point was not – usually – to use Mandeville as a source for information about the reality of fifteenth-century Jerusalem, since, as we’ve seen, this wasn’t the point of pilgrimage writing in general. Mandeville’s version of Jerusalem was already multi-era and multi-source, so mingling it with later pilgrim experiences means that the late-medieval Jerusalem-on-the-page becomes what Anthony Bale calls ‘the perfect simulacrum, a copy whose original had long since vanished, if it had ever existed’. So while there’s of course a certain overlap between Jerusalem-on-the-page and Jerusalem-in-the-world, the former was what pilgrims were aiming to describe when they copied from or drew on Mandeville’s description of Jerusalem, whether they did it with Mandeville as their direct source or whether they were copying other pilgrims who had themselves drawn on Mandeville. Bale coins the term ‘meme Jerusalem’ to describe this phenomenon.

But outside the ‘meme Jerusalem’ and beyond the Holy Land? Well, I started out by saying that it was rather brave to attempt an introduction to late-medieval pilgrimage writing, and that’s because it’s quite … elastic as a category. As Harff’s Reisebericht shows us, there was scope for pretty much whatever you wanted to include when you sat down to write about your pilgrimage. And while Harff might start his account by describing himself as ‘ritter geboren’ [knight by birth], he finishes it by asking his audience to pray for the pylgrym, weech wijser, ind dichter [pilgrim, guide, and author]. Just as he can be many things at once, so can his Reisebericht – and so can anyone else’s.

Image Permissions

- Digital.Bodleian (images from MS Bodl. 972 and Arch. B c.25): Creative Commons non-commercial license, with attribution (CC-BY-NC 4.0). Images © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

- Wikimedia Commons (Crucifixion group from Morken-Harff): Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-SA 3.0). Photo: Heinz Rade.

- Wikimedia Commons (Schloss Harff): Public Domain from the collection of Ludger Allhoff.

- Wikimedia Commons (Tagebau-Garzweiler): Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License (CC-BY-SA-3.0). Photo: Arne Müseler.

About the author

Mary Boyle is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in Oxford’s Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and a Junior Research Fellow at Linacre College, Oxford. She is the author of Writing the Jerusalem Pilgrimage in the Late Middle Ages (DS Brewer, 2021).

The digital edition of MS Bodl. 972 will be launched on 5th May 2021.

4 Replies to “Arnold von Harff: Knight, Pilgrim, Guide, and Author”

Comments are closed.