Report on an In-Depth Crash-Course on the History of ‘the Book’ with Péter Tóth by Alice Lanyue Zhang (MSt. Modern Languages, 2025)

This session of the History of the Book seminar at the Weston Library, led by Péter Tóth, focused on understanding the development of the Bible in its layout, languages, and content from the very early scrolls to the numerous modern printed editions. Each of the students was asked to bring along an edition of the Bible to compare and contrast what elements might have been retained throughout the traditions and what might have changed in modern printing and editorial practices. This 3-hour-long session was divided into 3 lecture sections looking at different major stages of the Bible in its transmission and production, and each section was followed by a short manuscript viewing session looking closely at Bible copies from different locations and historical periods.

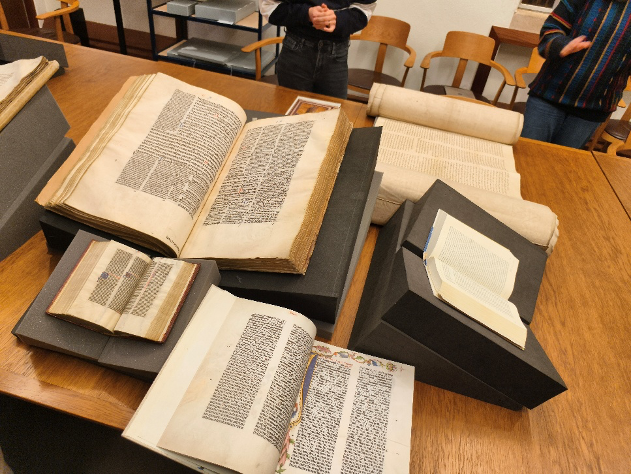

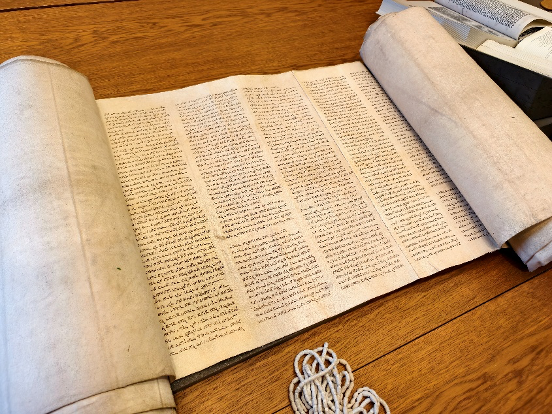

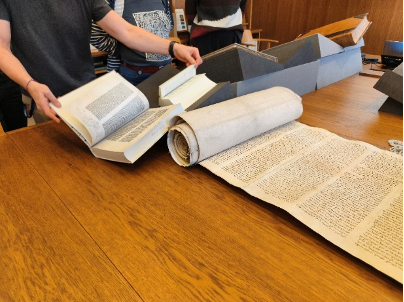

As an introduction to the session, Péter first presented us with three Bible copies representing the two ends of the material history of the Bible. The first item is a massive, carefully made Torah scroll in Hebrew (Figure 1) from, very interestingly, a 16th-century synagogue in southern China by the local Jewish community. Despite the late production, its scroll formatand its content of the Pentateuch make it a perfect indication of what the earliest Hebrew Bible would look like, which has also been proven true by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Its painstaking production, substantial size and difficulty of navigation also transformed the very act of reading into a ritual demanding careful handling and a mastery of the scripture. Only selected people are allowed to read the scroll, without direct touching, due to its sanctity. The second item was a facsimile of the Gutenberg Bible, with the last item being Henrike’s Die Bibel in gerechter Sprache (a Bible edition taking linguistic diversity and inclusivity into serious consideration). The former marks the beginning of the printed era of Bible production, whereas the latter marks the latest stage in our time. In contrast to the Torah scroll, the printed books make the Bible a much more open and accessible text with much easier navigation, increased portability and mass production. By laying these items side by side (Figure 2), we directly witnessed the huge transformation that the Bible and its materiality have gone through across history, which is exactly the topic of today.

The first section introduced the first translation of the Hebrew Scripture, i.e. the Septuagint, in Ancient Greek, done by seventy-two (always remember the ‘two’! emphasised by Péter) Jewish Rabbis commissioned by Ptolemy II around the early 3rd century BCE. It marks the beginning of the complete integration of the Old Testament into Hellenic Culture and the following reconciliation between Hellenic Greek mythology and Jewish Monotheism. But more importantly to this session, it also represents the start of the Hebrew Bible reaching outside of the Jewish community, rendered legible and understandable for its new audiences by translation – one of the two crucial elements driving the wide, cross-cultural dissemination of the Bible and its material transformation that came along, as Péter argued. In its own time, the Septuagint already kick-started a wave of translational attempts among native Greek-speakers who were unhappy with the Rabbis’ command over the languages. We see Aquila’s extremely literal translation prioritising the Hebrew syntax, Symmachus’ elegant rendition of the Scripture into Homeric Greek, and Origen’s Hexapla critically comparing all major Bible translations circa 250-60 AD. The Septuagint became even more profoundly influential as numerous scribal practices it took became traditions adopted by many later manuscripts, and various important biblical vocabulary and concepts it established are still deeply embedded in Western languages today.

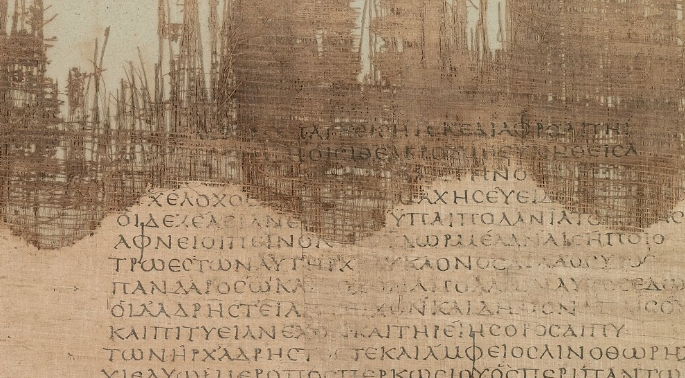

In the following manuscript-viewing session, we began by examining the earliest examples of layout formats in Western tradition. The first example is a fragment of Homer’s Iliad in the form of a luxury papyrus roll (Figure 3), produced roughly in the 3rd century AD. The verses are copied in two columns, annotated critically by the Alexandrian scholars. It shows us some of the earliest efforts to consolidate the Homeric verses and produce a critical school edition, which would become the blueprint for formatting the Greek Old Testament. Péter then presented us with two examples of the ultimate form of this early editorial tradition. The first one is a facsimile of an early 11th-century critical edition of the Iliad (Figure 4), and the second is a facsimile of the Juliana Anicia Codex (Figure 5 & 6). In both examples, we sawthe carefully glossed text being preceded by a series of complementary content: biographiesand portraits of the author, introductory treatises and/or summaries, credits of editors, table of contents, title, etc. We then examined two early codices, one of the Septuagint and one of the Book of Psalms, where we observed the continuation and influences of the editorial and layout practices in the classical texts. With the Book of Psalms, we also found modifications and additions of elements to suit the specific liturgical needs (e.g., calculation tables and calendars). From here, we developed a clear idea of what the early standardised format of the Scripture would look like, which led the way to the next sections focusing on its wider transmission.

The second lecture focused on the second and last core element that drove the transmission of the Bible – the New Testament. It played a crucial role in the process due to its missionary nature to spread Christianity and carried the Old Testament along with it, formulating the Bible we know today. Péter gave us a general introduction to the evolution of the New Testament, where it began as simply a record of Christ’s sayings and teachings. With the evangelists adding context and expanding the text, it developed into the popular genre of gospels that went far beyond the canonical Four Gospels that are now in the Bible. We also saw the emergence of apostolic writings, such as numerous epistles and the Acts of the Apostles. With such a rich pool of literature came the need for solidification. Thus, around the 4th-5th centuries, the canonisation of the New Testament gradually took place. The distinction between ‘canon’, accepted texts and ‘spurious’, rejected texts became common and concepts like the ‘apocrypha’ were established.

What also came with the New Testament is the rise of the codex. Originating from ancient Roman wax tablets, the codex was adopted by Christians as the main format. The change to codex format allowed more writing space, easier navigation for liturgical uses and likely contained an ideological undertone of distinguishing the new Christianity from the pagan scrolls. The material also transitioned from papyrus to parchment due to its durability and reusability, as well as the papyrus shortage at the time. Yet the change of material format doesn’t necessarily entail a change in editorial practices. For instance, in one of the earliest complete Bibles, the Codex Sinaiticus (ca.350AD), it still retained the 8-column layout of the papyrus scroll. At the end of this lecture session, Péter discussed the practical use of the gospel books as a common form of New Testament transmission, in which we saw the development of canon tables that compare the narrative units across the Four Gospels, something we would see very frequently very soon.

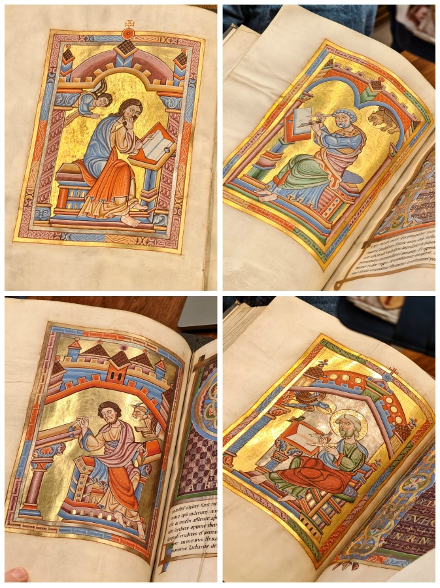

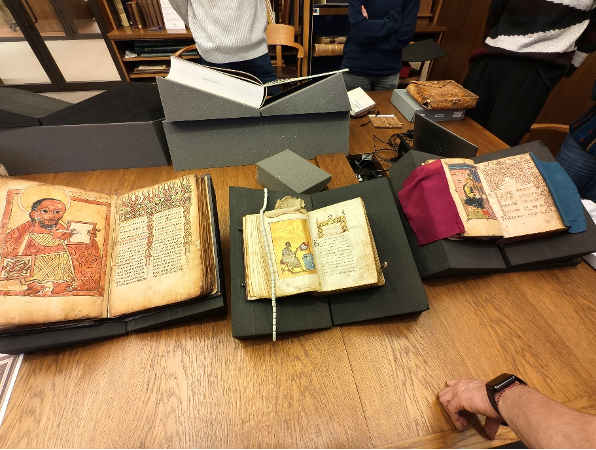

Accompanying the lecture, in the next manuscript viewing session, we saw various copies of the New Testament that were produced in different regions and different periods. As pointed out by Péter, canon tables (sometimes with a user guide) became widely present in almost all gospel books, followed by more ‘traditional’ elements such as a list of chapters, portraits of authors, and abstracts for each book. One of the highlights during this session was the comparison Péter presented with three different codices of the Gospels produced a few hundred years apart: one Ethiopian, one Greek and one Armenian (Figure 7). Each copies are decorated with cultural iconographies in local artistic traditions, yet the layout and format of the codex remained the same. From here, we see with our own eyes the wide, cross-cultural dissemination of the New Testament and the relative stability of itsstandardised textual and material production.

The last lecture focused on the history of the Latin Bible for its profound linguistic, cultural and spiritual influence in the Western world. The need for a Latin Bible started with the Latin-speaking Romans in North Africa around the 2nd-3rd centuries AD due to the limited Greek influence in the area and the increasing demand to understand Christian texts. The translation likely began sparsely with liturgies before developing into full text, as we found notes of oral translation in lines or margins of the Gospel books at the time. The early translations of the Bible were often adapted for regional dialects and corrected against unfounded Greek manuscripts, leading to the mixing of textual traditions and the overwhelming parallel existence of different versions by the 4th century. Therefore, Pope Damasus commissioned Jerome in 382 AD to polish and unify the Old Latin Gospels and later the Old Testament, producing the foundation of a standardised Latin Bible despite its controversial reception. In 585 AD, Cassiodorus and his monastery developed a full Bible based on Jerome’s work, which is preserved in the Codex Amiatinus. Finally, in the court of Charlemagne, with the unification of the Carolingian Empire, a standard full Latin version was produced and successfully circulated across the empire from ca. 800 AD, marking the consolidation of the Vulgate Bible.

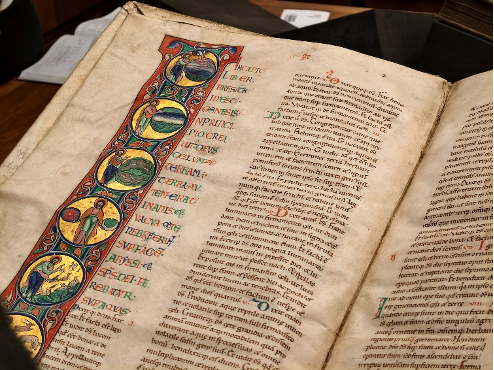

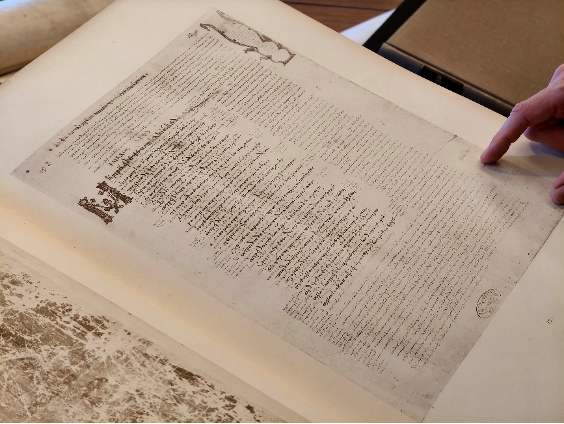

In the final manuscript viewing session, we saw several different copies of the Latin version of the Bible (Figures 8 & 9). In these copies, we continued to see a series of fairly standardised layouts and editorial practices, i.e., all the elements mentioned above, that could trace back to as early as the classical textual traditions and the emergence of practical gospel books. We also examined several beautiful and interesting illustrations. For instance, in a Carolingian gospel book, the portraits of the four evangelists formed a ‘stop-motion’ of the writing process (Figure 10); the historiated initial of Genesis in one Bible codex illustrated the seven days of creation (Figure 11). Eventually, we circled back to the facsimile of the Gutenberg Bible that symbolises the revolution of the printing press, and the beginning of modern Bibles.

And thus concluded the 3-hour journey on the history of ‘the Book’.