A report by Tamara Klarić, research intern during Michaelmas 2025 with Henrike Lähnemann

The Isar and Thames rivers have more in common than might appear at first glance: both shape the image of the cities through which they flow, and both influence the life that takes place in these cities. Munich residents enjoy walking along or swimming in the Isar or meeting there for coffee. In Oxford, too, a lot of activity takes place on the Thames and Cherwell: numerous college rowing teams train on the water, punting boats regularly pass by walkers, and on the banks you encounter rowing team coaches as well as runners and cyclists. At the same time, not only do almost 1,200 km separate these rivers, but also (university) culture and atmosphere: Munich and Oxford – both are cities renowned, innovative universities, but these are integrated into the cities in very different ways. I have been living in Munich for over two years now and if I had to describe the city, I would probably describe it as modern, dynamic and efficient. In my mind, Oxford is both traditional and vibrant, cosmopolitan and self-contained.

1 My background: “Cultures of Vigilance”

I am employed by the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC) 1369 “Cultures of Vigilance” at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, which deals with the connection between personal attention and supra-individual goals. Specifically, we understand vigilance as “the coupling of individual attention, firstly with culturally mediated, supra-individual goals and, secondly, with concrete options for action and communication.”[1] The projects, which cover a wide range of disciplines, are divided into three thematic areas: transformations, spaces and techniques. The historical sub-project in which I am writing my dissertation is assigned to the first area. Together with my colleague John Hinderer and under the supervision of Prof. Dr Julia Burkhardt and PD Dr Iryna Klymenko, I am analysing vigilance in pre-modern Benedictine monasteries using the example of the Bursfelde Congregation. While John Hinderer is investigating how the congregations of Santa Giustina di Padova and Bursfelde sought to regulate different areas of monastic life, I am examining the “long” 16th century (approx. 1500 to 1618). My focus is on the recesses of the Bursfelde General Chapters (i.e. the written resolutions of the annual meetings of all abbots) and on the letters of the leading abbots around 1600. After suffering heavy losses due to the processes catalysed by the Reformation and after the Council of Trent, the Bursfelde monasteries found themselves in a phase of restabilisation and reconstruction during this period. The leading abbots of the congregation sought to expand their sphere of influence, which can be clearly seen from the sources: they not only provide information about how the abbots worked to (re)gain individual monasteries, but also about the strategies they developed towards external actors and the measures they took to restore internal unity. When it comes to the question of communication in times of uncertainty, I am particularly interested in the written perception of uncertainty, the resulting discourses in the correspondence, and any adaptation processes within the congregation. Underlying all of this is the vigilance of individuals and their commitment to serving the community.

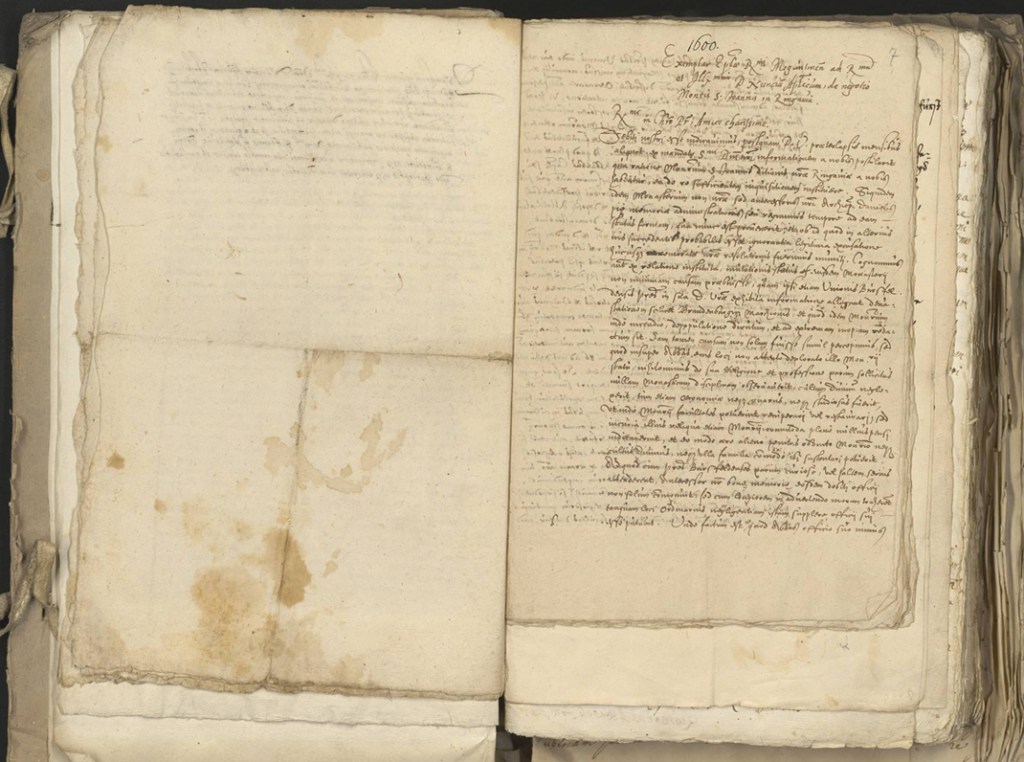

The letter shown here as an example is part of a dispute between the abbots of the Bursfelde Congregation and the archbishop of Mainz over the restitution of the Johannisberg monastery in the Rheingau (Diocese of Mainz). In this letter to the Apostolic Nuncio from 1600, the Archbishop of Mainz, Wolfgang X von Dalberg (in office 1582–1601) reports on the desolate condition of the monastery. The monastery was destroyed in 1552 and dissolved in 1563 by the former archbishop, Daniel Brendel von Homburg (in office 1555–1582). Since 1596, the abbots of the congregation had been trying to bring the monastery back into their union and had also approached the Curia in this regard. The present letter is a reply from Wolfgang X to the Apostolic Nuncio, in which he defends himself against the accusations of the Bursfelde abbots, justifies the behaviour of his predecessor and describes his own: He attributes the establishment of a secular administration not only to the devastation wrought by the Margrave of Brandenburg, but also to the negligence of the former abbot and the inadequate supervision of the Bursfelde Union. He justifies the abbot’s dismissal and the temporary secular administration of the monastery as necessary measures for debt settlement and the restoration of religious life in accordance with the rules. At the same time, he rejects the accusation of having abused the monastery for his own gain and emphasises that he acted lawfully and in the interests of the monastery. Finally, he asks the Nuncio to inform the Bursfelde Union of this view and to prevent further complaints.

Vigilance is evident in several places in this letter: As the archbishop’s vigilance towards monastic conditions, it can be read as a duty of ecclesiastical authority. According to Wolfgang X, however, its absence is the central cause of monastic decline, as he describes how the abbot failed to fulfil his official duties and how the Bursfelde abbots also failed to adequately fulfil their supervisory duties. At the same time, he emphasises that he is willing to re-examine the situation at the monastery should changes become apparent – vigilance is thus understood as a continuous duty.

At the conference “Zwischen Erneuerungswunsch und Traditionsbewusstsein. Klosterreformen im Alten Reich (1400–1700)” organised by Carolin Gluchowski and Marlon Bäumer in March 2024, I met Henrike Lähnemann and applied for a research internship with her. For the Michaelmas term of 2025, I was then given the opportunity to travel to Oxford for three months through this research internship. This time was not only extremely productive for me professionally, but also personally: as a woman with a non-academic and migrant background, it had long been unimaginable for me to be able to live and work here for three months. Now I am faced with the difficulty of summarising the significance of three intense months in just a few paragraphs. It is a task that is actually impossible. However, with the help of a few photographs, I would like to try to at least come close to doing so:

2 Arrival

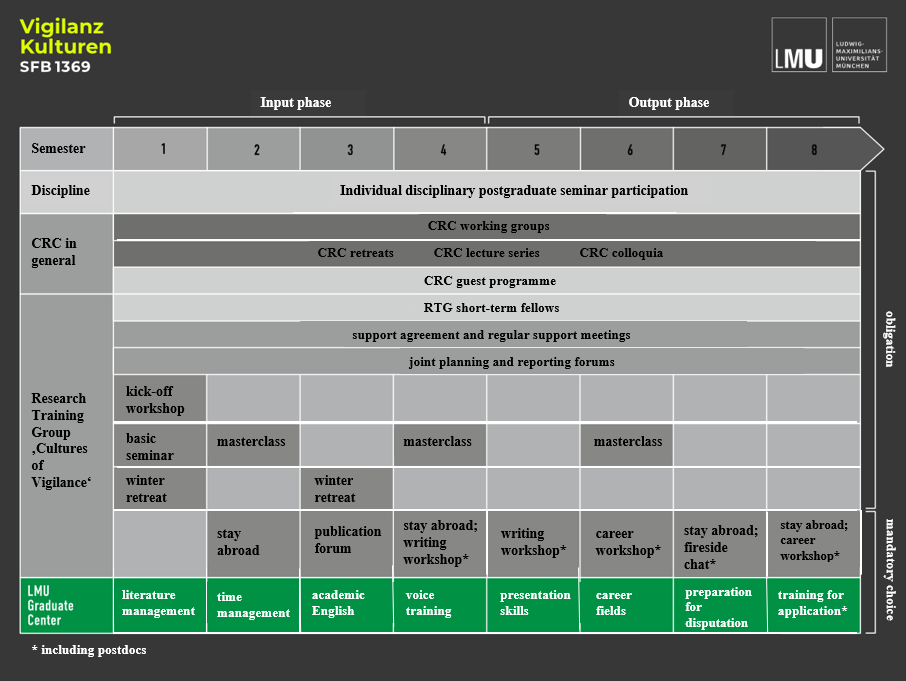

I decided to arrive at the end of September, two weeks before the start of the term, so that I would have some time to find my way around the city and gather my first impressions. I am very privileged to be funded by an CRC in Germany: doctoral students are not employed by the departments but are funded by the German Research Foundation and thus by third-party funds. This meant that I didn’t have to apply for scholarships to be able to afford a stay in Oxford but could be funded by my employer. And within the framework of an SFB, stays abroad are possible; in our case, they are even supported as a possible part of our doctoral programme through the integrated Research Training Group:

I was accommodated in a private house in New Hinksey, just south of the city centre. The reason for my decision was that I wanted to build a second, non-university environment for myself, where I could experience as much of everyday life in Oxford as possible. And I don’t think I could have made a better decision: my landlord, who also lives in the house and sublets two rooms to guests, is an incredibly open and friendly person who invited me to barbecues with his family and regular music evenings with his friends. Oxford quickly felt like home!

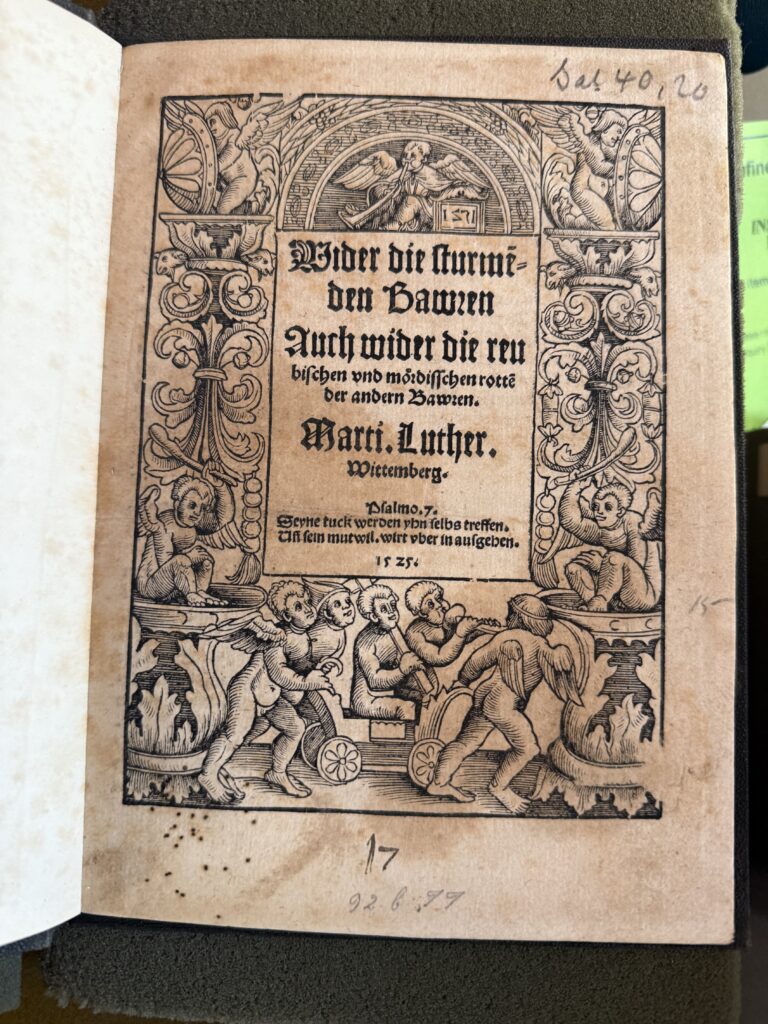

During these last warm and sunny days of late summer, I spent a lot of time exploring the city and its surroundings. The area between Oxford and Hinksey in particular, but also Christ Church Meadow, the University Parks and the paths along the Thames between New Hinksey and Iffley are ideal for walking and running. During this time, I also had the opportunity to participate in the conference “’In our own tongues’: The Medieval Vernacular Bible and its European Contexts”, make initial contacts and friendships, and got to get to know and accompany the participants of the Summer School “Opening the Archives” organised by the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes. The participants’ task was to prepare the digital edition of the pamphlet “Against the attacking peasants” (Martin Luther, 1525): they created the transcriptions, a first draft of the online edition, and curated a small exhibition on the topic in the Voltaire Room of the Taylor Institution Library.

The Michaelmas term 2025 also marked the start of seminars and actual university life in Oxford: through Henrike Lähnemann, Marina Giraudeau, the other intern for the term, and I were affiliated with St Edmund Hall College, and our admission as guest members for this term enabled us to participate in MCR social events. These events, which go hand in hand with belonging to a college, are something I am not familiar with from university life in Germany: Of course, there is also the opportunity here to join a hockey or volleyball group through university sports, go to the gym or go swimming. However, such events are inter-university, as we do not have an equivalent to the colleges. On the one hand, I liked how familiar the environment was, especially for undergraduates, but at the same time, from a German perspective, it is a little strange to be accommodated in college rooms: in Germany, students are not even obliged to live in the city where they study!

Similar to my job in Munich, where I am also involved in the chair’s advanced seminar, I was allowed to participate as an intern in Henrike Lähnemann’s DPhil colloquium in Oxford, where I was able to present my own dissertation project. As an early modern historian with a background in German studies, I particularly benefited from the feedback of the other participants, as most of them have a background in medieval studies and gave me valuable advice on working with different manuscripts. The approach to vigilance being researched by the SFB also met with lively interest and opened up further perspectives: How does our view of the sources change when we look for attention or vigilance in them? What new perspectives open up for us? Where do we encounter limitations when dealing with vigilance? We addressed these and other questions in the discussion that followed my presentation.

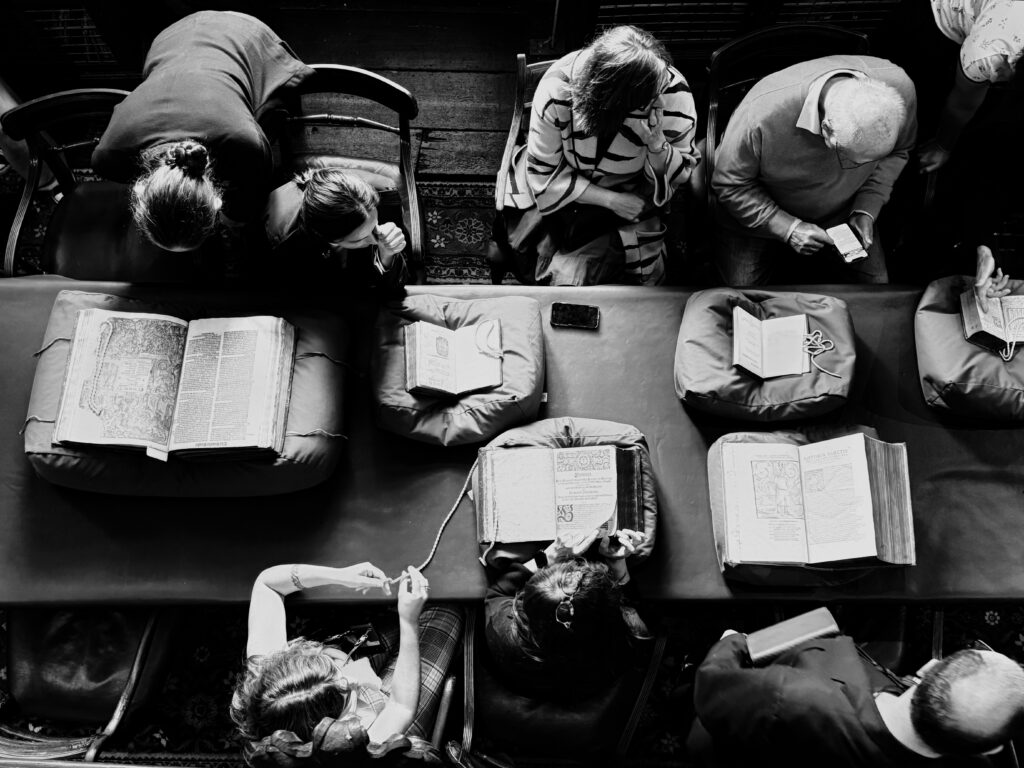

In addition to the colloquium, I participated in the seminar “History of the Book. Method Option 2025/2026”. Under the direction of Henrike Lähnemann, we dealt with different aspects each week of the term: palaeography, book development, book production and printing, textual transmission, the function and structure of libraries, and the growing field of digital humanities are just some of the topics that were the focus of attention. The emphasis was on medieval and early modern works, in particular the aforementioned Reformation publications. What I particularly liked about it, however, was that we were able to work on this seminar very much according to the principle of show-and-tell, which meant we worked in a very practical way and very close to the sources. Henrike Lähnemann invited other academics to many of the sessions, which also brought us into contact with different areas of research and work.

This work was supplemented by the “Medieval German Graduate Seminar” which is jointly organised by the three German medievalists Henrike Lähnemann, Almut Suerbaum, and Annette Volfing, taking place in Michaelmas Term in Almut Suerbaum’s college Somerville, in which we dealt with Ulrich Richental’s Chronicle of the Council of Constance (second half of the 15th century). Here, too, we dealt with different topics each week, and the discussions on the different manuscripts and their characteristics, on the boundary between historiography and literary works, but also on the historical background were particularly beneficial for my own research. These two seminars enabled me to deepen my knowledge of medieval and early modern book production and the critical approach to manuscripts, as well as my background knowledge of the ecclesiastical political circumstances of the 15th century, which ultimately led to the Reformation and thus to my project.

3 Working with early modern printed books and their digital editions

My research internship in Oxford focused on Reformation pamphlets, especially those by Luther from 1525, which are now held by the Taylor Institution Library. The aim was to bibliographically record, describe, document and compare the copies. It was particularly interesting to see how much such a pamphlet can reveal about the history of its creation and distribution. Whether it is the mirrored year on the woodcut, which indicates that it is a pirated edition, or the condition of the paper, which allows us to make a statement about how often the pamphlet was probably read and commented on – it is hardly possible to get any closer to the history of its reception!

Here, too, it was not difficult for me to establish connections to my research topic and, in particular, to vigilance: Reformation pamphlets can be read as media of heightened attention that respond specifically to perceived grievances, threats and crises. In 1525 in particular, a year marked by uprisings, uncertainty and escalating conflicts, these prints served as normative guidance for their authors and recipients but were also an expression of a changing world. A detailed analysis of the material properties, visual language and textual exaggerations revealed the extent to which practices of vigilance were not only negotiated but also generated. In this sense, the prints can be understood as part of an early modern culture of vigilance in which attention was to be directed, judgement demanded and collective willingness to act established. Furthermore, the comparison between the corpus of letters I am working on for my dissertation project and the printed pamphlets of the Reformation period sharpened my eye for media differences in vigilance practices: while the letters primarily describe a community-oriented, internal vigilance, the pamphlets aimed at public attention. What both have in common is that they provoked reactions and processes of adaptation.

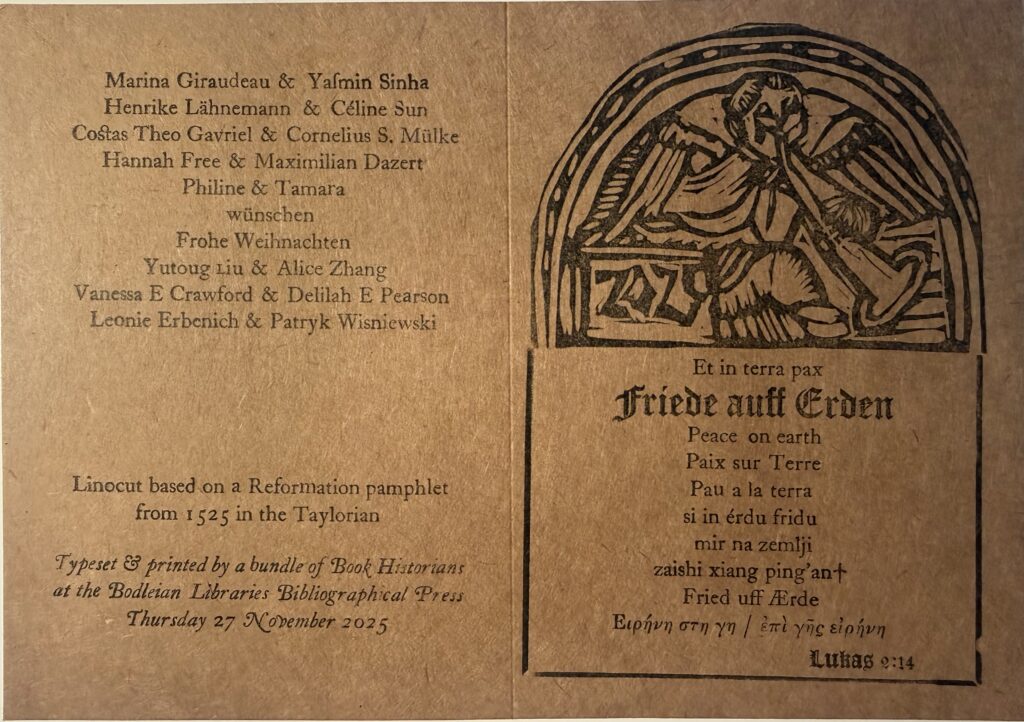

However, I particularly enjoyed working on the online edition, which allowed me to become more familiar with Oxygen and coding in TEI P5 XML. Here, I was able to adapt the translation of the online edition of the pamphlet to the print version. A major highlight of this work was the launch event for the edition on 28 November, where I had the opportunity to read aloud from “Wider die mordischen und reubischen Rotten der Pawren” together with several others.

4 Oxford, snow globes and strolls between libraries and cafés

I was very lucky to be able to experience Oxford in the run-up to Christmas. From mid-November onwards, colourful lights decorated the streets, the many windows of the cafés and shops were decorated for Christmas, and the Oxford Christmas market – which, as a German, made me feel particularly at home – opened its doors at the end of November. From there, you can go straight to Blackwell’s, Oxford’s most beautiful bookshop, and do all your Christmas shopping after work and between mulled wines. The only limit I faced here was the weight of my suitcase: 23 kg as the airline’s limit is really not much after three months in Oxford!

Someone once said to me that Oxford is a bit like a snow globe: a self-contained system, a bubble that extends mainly over the university and forms a world of its own. And that’s true, in a way. Oxford invites you to immerse yourself, drift along and forget the outside world for a while. And, similar to the snowflakes in such globes, the mentality here is not really tangible: I talked to several people about their impressions of the city, many of whom have been living here for several years. What they all had in common was that they incredibly appreciate how much the city thrives academically; it’s almost as if you can watch it grow. This is mainly because research is immensely important and the city has developed and continues to develop around it: researchers come, learn and teach, exchange ideas and leave again, but the network remains. Although the city is not that big at its core, you quickly notice how extensive the network that has formed here is and how it continues to grow. I was told that Oxford is a hub to which many people return at some point, and I like that idea. Apart from the contacts I made during my research internship, I was also able to use the time to meet up again with scientists I already knew from other contexts. So, during these months, I also had the opportunity to closely integrate my research internship with my dissertation project and work on two projects at the same time!

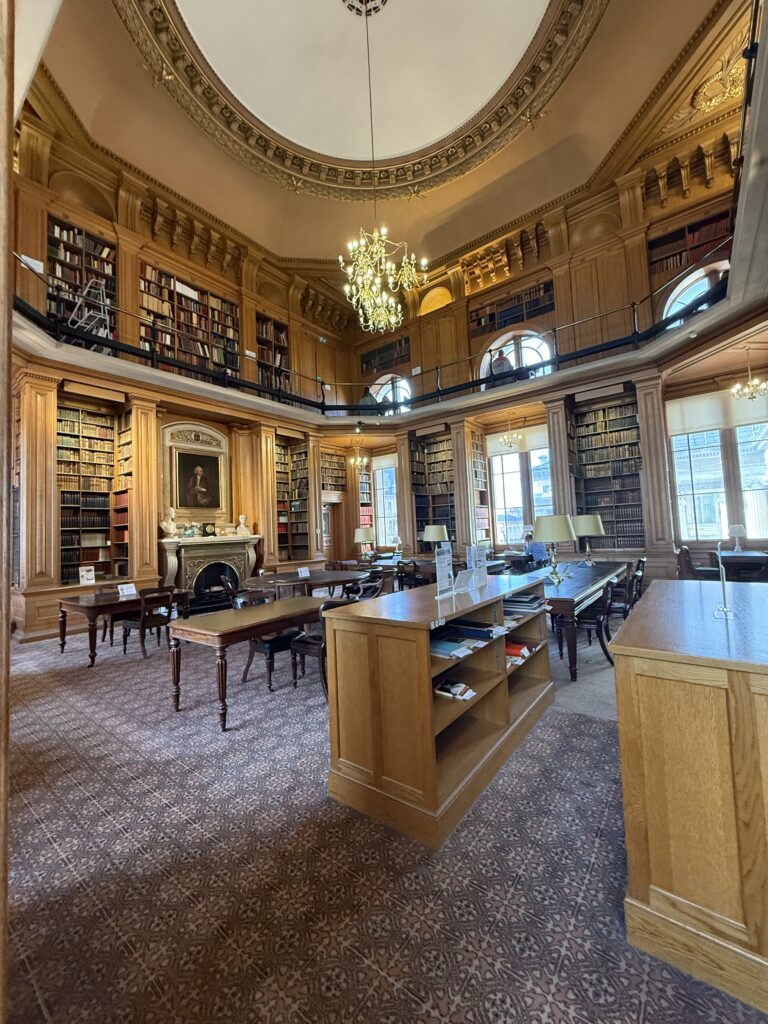

Just as valuable as the contacts I made and maintained are all the libraries there are to explore. Regular spots and get-togethers to work together are great, but seriously: use your reader’s card and visit as many libraries as you can! Work in them, look at the books, borrow manuscripts and take the opportunity to immerse yourself in topics that may not initially have anything to do with your field of research! This opens up so many new project opportunities, and even if you don’t have time for them, working with these sources is helpful as they may reveal new perspectives on your own projects!

In addition to the opportunity to immerse yourself in the sources, you can also take part in the “Medievalists Coffee Mornings” at the Weston Library on Fridays, where you can enjoy coffee or tea and biscuits while listening to a short lecture on selected sources from the Bodleian Collections. The speakers change, so that sources from different eras and disciplines are presented, allowing you to engage in conversation with a wide variety of scholars. A little tip: the terrace, from which you can look out over Oxford, is also well worth a visit in this context!

As a very student-oriented city, Oxford has a multitude of cafés and pubs, all of which are worth trying out. My regular haunts were Jericho, the High Street, of course, as well as the surrounding streets and the area around Cowley Road. At the same time, it should be noted that even the most beautiful cafés and pubs are only half as great without friends. The idle hours of work on the weekends, which you sometimes have to put in, are much easier to bear after a coffee together at “The Independent”, for example! What’s more, the time in between can be put to excellent use to talk to others about your own projects and possible synergies!

P.S.: Coffee stamp cards are really worth it! I collected a few of them myself at my favourite café and got a pumpkin spiced latte or two for free!

5 Farewells and Returns

The twelve weeks I spent in Oxford flew by incredibly quickly. Looking back, this time was not only marked by my own intensive research work, but also by a constant sharpening of my attention: for sources, for methodological questions and for different scientific environments and their social practices. The research internship thus offered me the opportunity to reflect on and further deepen central questions of my dissertation project in a new context. Once again, it became particularly clear to me that vigilance can be understood not only as an analytical concept, but also as an attitude that shapes one’s own everyday academic life – whether in dealing with sources, in exchanges with colleagues, or in exploring new environments. At the same time, I had the opportunity to meet many wonderful people who greatly influenced my stay in Oxford and made this time unforgettable.

What am I taking back with me to Munich from Oxford? In addition to the many books, gifts and memories, there are also ideas for further projects: whether these are ideas for creative writing or for introducing meetings such as the Medievalists Coffee Mornings into my own working environment in Munich – I am looking forward to the coming months, during which I will continue to draw on this stay!

Finally, what could be more fitting than a formal dinner at St Edmund Hall to mark the end of my stay? I was even lucky enough to be invited to the undergraduates’ Christmas dinner. Together with Marina, I had the privilege of sitting at the high table with Henrike Lähnemann, enjoying interesting conversations and experiencing the Christmas traditions of Christmas crackers and singing on chairs!

P.S.: Stamp cards are also worthwhile when it comes to farewells: I have just started a new one at my favourite café, so I definitely have to come back to Oxford! Perhaps this is my personal Oxford equivalent of the coin in the Trevi Fountain – it has worked for Rome in any case!

[1] Brendecke, Arndt: Warum Vigilanzkulturen? Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Ziele eines neuen Forschungsansatzes. In: Mitteilungen des SFB Vigilanzkulturen (01/2020), p. 11–17, here p. 16 (my translation).