by Caitlín Kane, Special Collections Curatorial Assistant New College

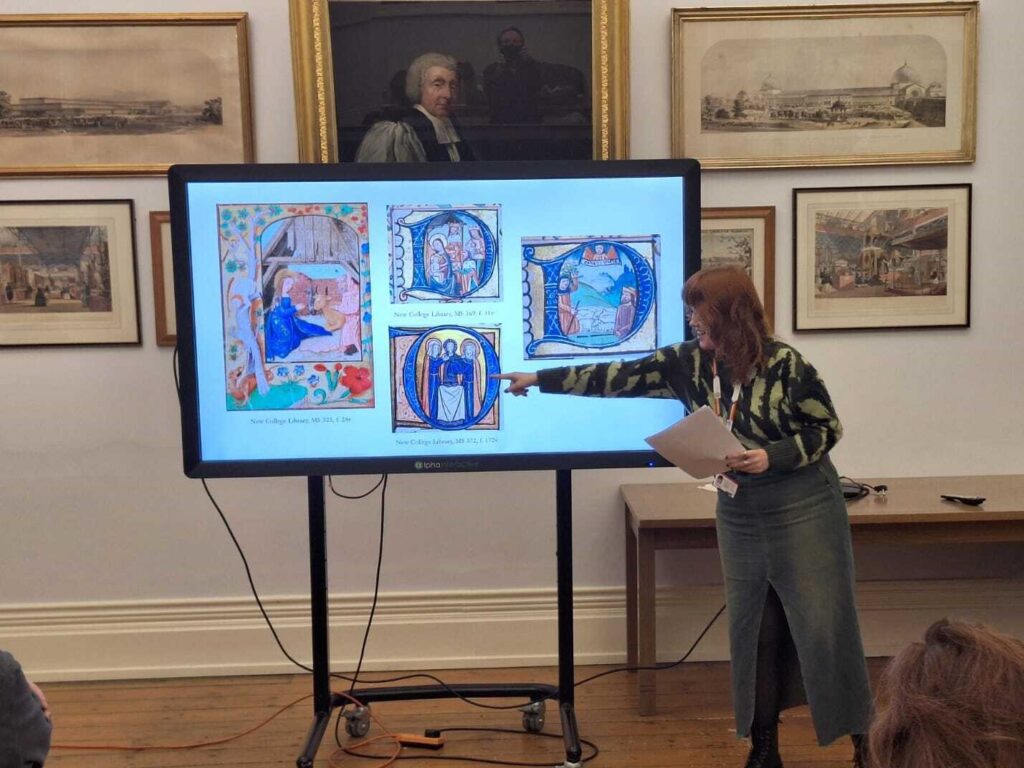

Back in February of this year, New College Library, Oxford had the pleasure of showcasing our wonderful collection of seven Books of Hours—beautiful manuscripts that once served as religious texts and treasured family heirlooms. Popular from the 14th century, especially in France, England, and the Netherlands, these were devotional texts that brought monastic routines into the daily lives of laypeople. Each typically included a calendar, the Office of the Virgin, Penitential Psalms, a litany, and the Office of the Dead, often decorated and customised to reflect the owner’s personal devotions. In collaboration with the Medieval Women’s Writing (MWW) Research Group, we hosted a workshop to show off, discuss, and examine these precious books. The event began with a talk by New College’s Special Collections Curatorial Assistant (that’s me!) on the significance of these books in studying lay devotion, particularly among women, and I shared tips on identifying their owners through text and decoration clues. Dr Jess Hodgkinson, New College Library’s Graduate Trainee, followed with a wonderful talk on her discovery of Eadburg in Bodleian Library, MS Selden Supra 30, thanks to innovative 3D recording technology from the ARCHiOx project.

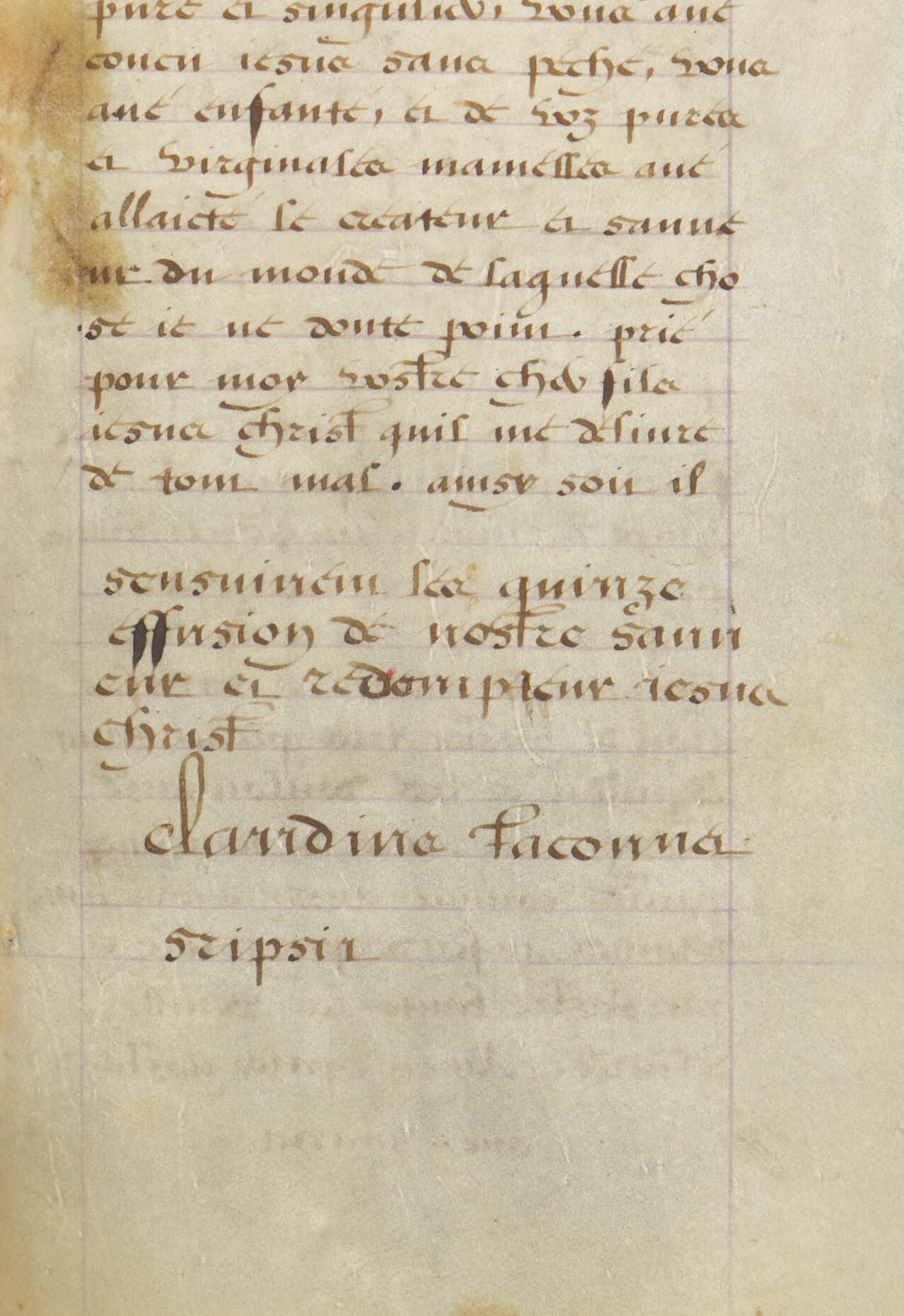

Participants then had the chance to examine the manuscripts up close. A particularly lively discussion arose from an inscription I had found just that week in MS 369, where we debated whether the scribe’s name was ‘Claudius’ or ‘Claudine’.

It was wonderful to see these books being enjoyed, given that many hadn’t been closely studied since their donation in the 1980s. The enthusiasm and insights from everyone involved have been invaluable, prompting further research and discoveries about the lives of their former owners, some of which I will share now.

MS 369: A FRENCH CONNECTION

MS 369 is a late 15th-century French book of hours, possibly Use of Amiens, written in Latin. The last eight folios contain prayers to the Effusions of the Blood of Christ, written in vernacular French, and signed ‘Claudius Taconnet sripsit [sic]’. I had originally thought the name was Claudine or Claudina, but a further inspection of the horned ‘s’ in ‘les’ and ‘jesus’ suggested otherwise. Although there is a record of a Claude Taconnet, a juror for the linen-workers, in Paris in 1586, it’s unclear at this stage if this is our same Claude. The inclusion of these vernacular prayers suggests they were intended for someone less familiar with reading Latin.

All manuscript images © Courtesy of the Warden and Scholars of New College, Oxford

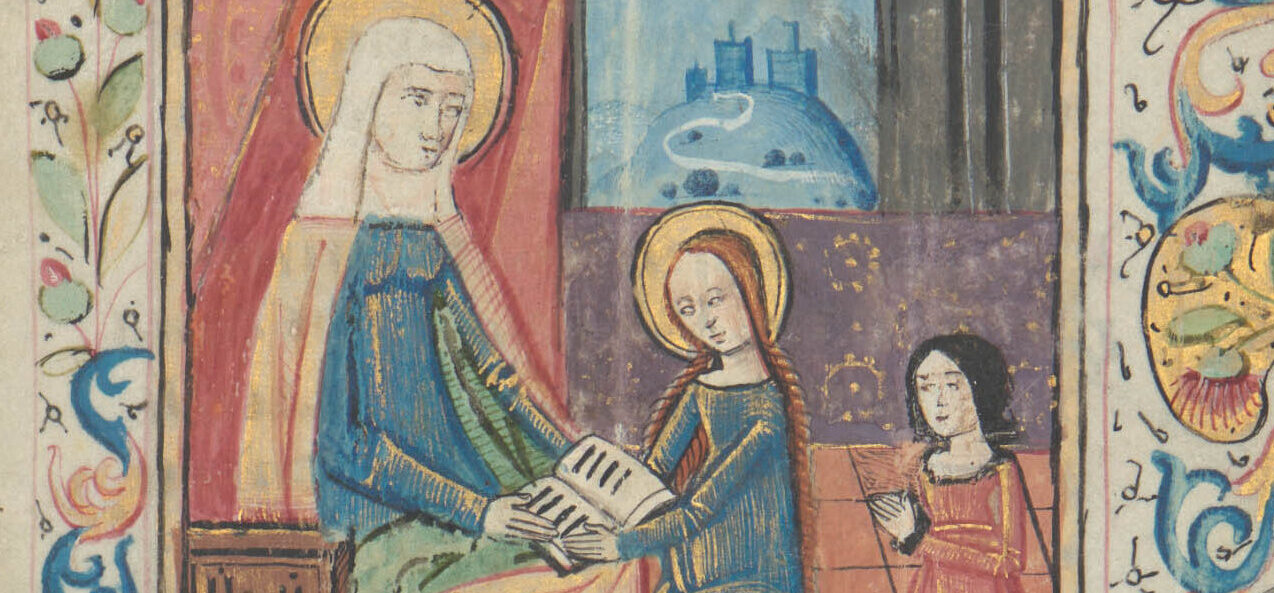

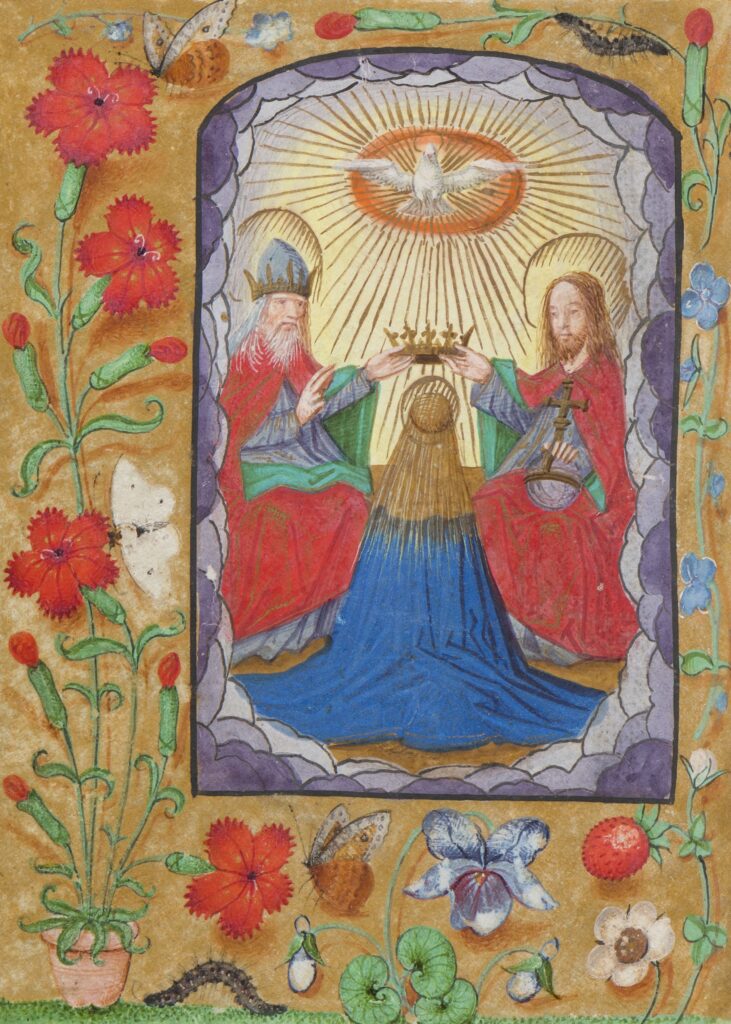

MS 369’s decoration is rich with burnished gold, floral borders, and miniatures. The face of St. John in one miniature has been worn away, likely through reverential touching or kissing of the page. This is commonly seen in books of hours, as the laity adopted not only monastic routines and prayers, but also imitated their priests in kissing holy images and books. As was pointed out to me during our showcase, a small figure depicted praying in an illumination of Saint Anne reading to Mary may potentially represent a member of Claude’s family or a woman for whom the book was originally commissioned.

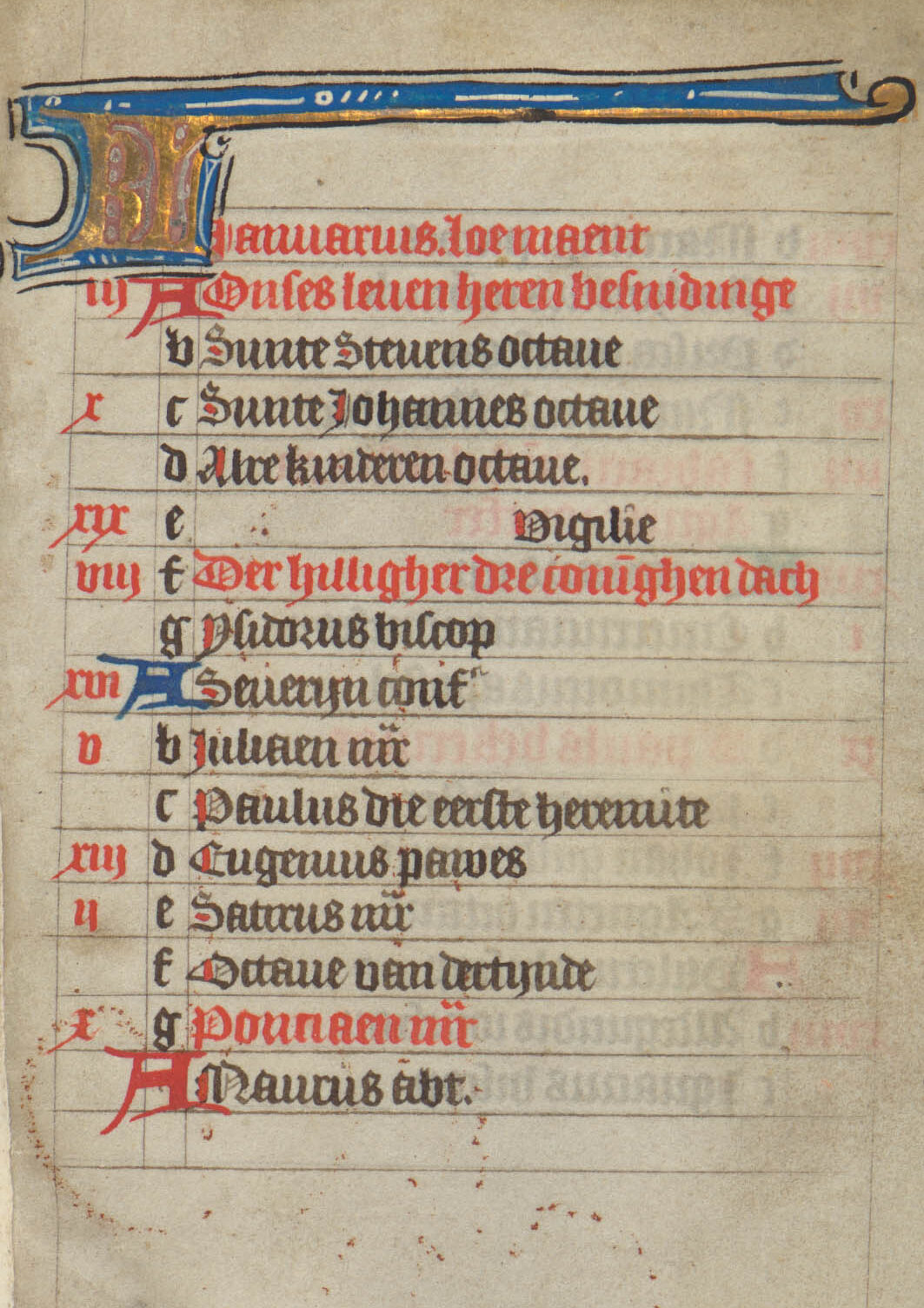

MS 371: HERETIC HUNTERS IN DRENTHE

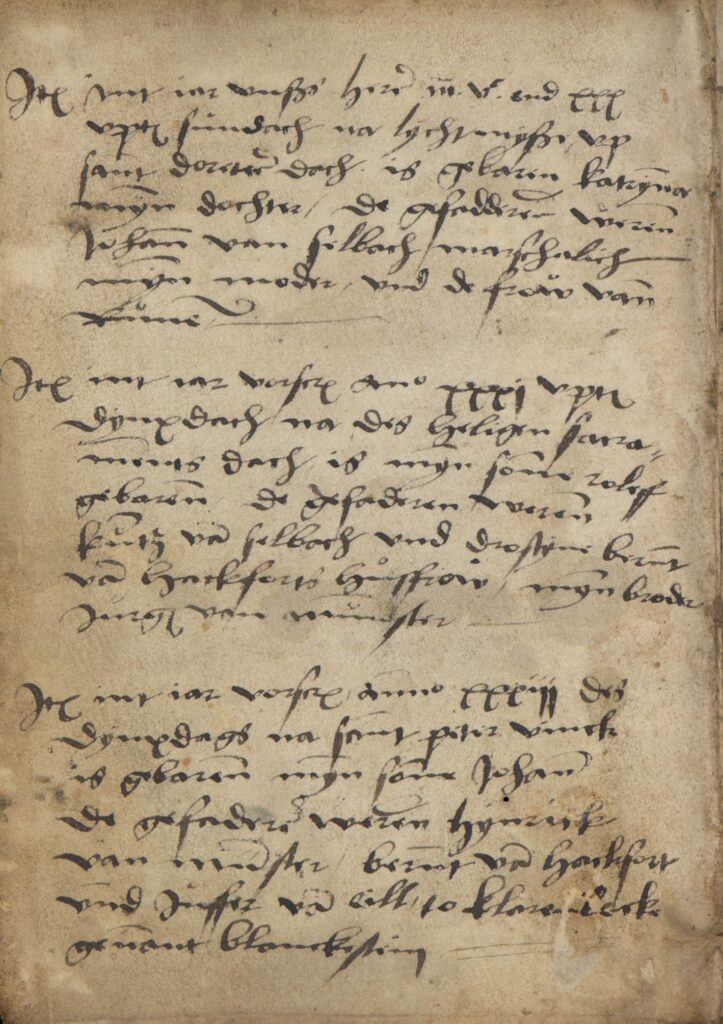

While preparing for our workshop, I thought Claude’s inscription in MS 369 would be the highlight. But thanks to the work of Prof. Henrike Lähnemann and Dr Friedel Roolfs, I was excited to discover that the inscriptions in MS 371 were even more intriguing. MS 371, a book of hours in the Middle Dutch vernacular, was likely made in a monastery in the Northern Netherlands around 1460-1480. Its calendar features saints linked to the dioceses of Utrecht, such as St Willibrord and St Walburga, and of Münster, including St Blasius and St George. This calendar and the decoration are strikingly similar to those in books of hours produced in the Benedictine double monastery of Selwerd in Groningen. Though the book’s exact origins need further examination, the endleaves record the births of Maria van Selbach and Roelof van Münster’s children from 1530 to 1538:

Item, in the year 1530, on Sunday after Candlemas, on St D.’s day, my daughter Katharina was born, whose godparents were John of Selbach, Marshal, my mother, and the wife of […].

Item, in the aforementioned year ‘31 on the Tuesday after Corpus Christi is my son Rolef born whose godparents were Kuntz von Selbach and the wife of Droste Bernt van Hackfort, my brother Jürgen van Münster.

Item, in the aforementioned year ‘33 on the Tuesday after St Peter-in-chains is born my son John whose godparents were Henry van Münster, Bernt van Hackfort and the young lady van Eill to Klarenbeck, called Blankenstein.

Item, in the year [15]34, on the 8th day after the birth of the BMV, on a Tuesday morning, my son Dirk was born whose godparents were my mother and Dirk van Baer.

Item, in the year [15]36 on the Eve of Corpus Christi my daughter Agnes was born, whose godparents were her brother Roleff and Jutta Smullynck.

Item, in the year [15]38 on a Tuesday after St Martin, my son David was born.

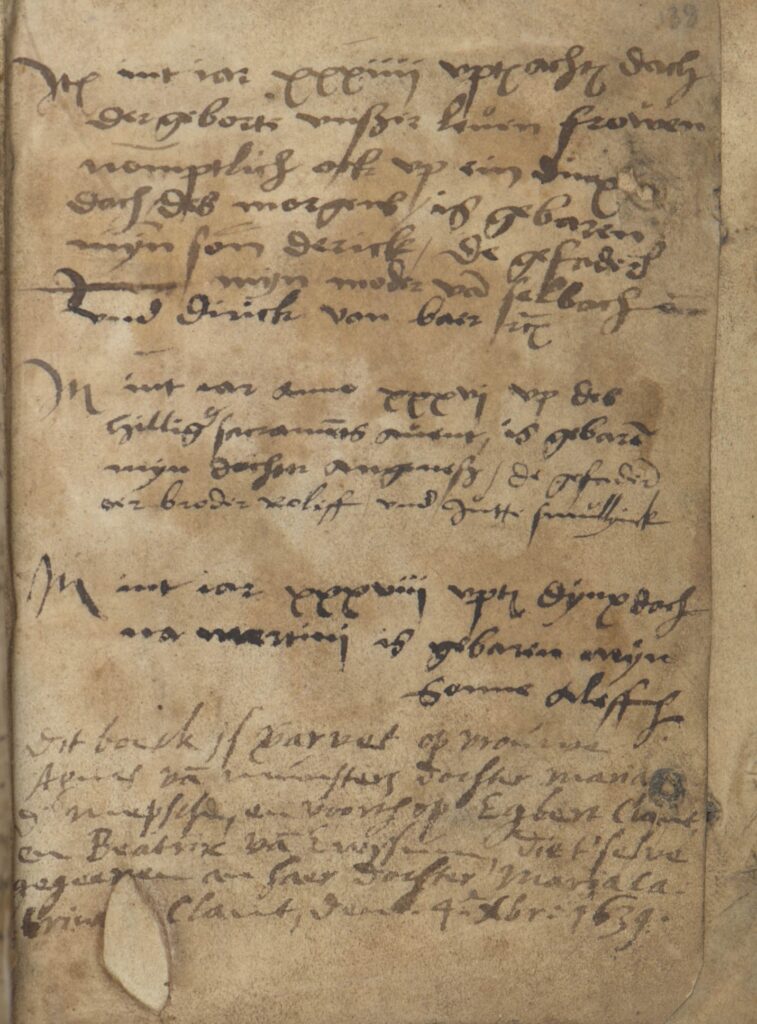

All the names are clustered around the castle Klarenbeck in the Duchy of Cleves and the now destroyed Duirsum Castle in Loppersum, in the border area between the Netherlands and Germany. Maria van Selbach, born around 1510, grew up in Terborg and later moved to Coevorden with her father Johan van Selbach, the Drost of Drenthe and Castellan of Coevorden, and her mother Jutta Schmullynk. After her marriage to Roelof van Münster, the couple eventually settled in Duirsum Castle, Loppersum, in 1540, which Roelof inherited from his wealthy mother, Bauwe Heemstra. Agnes, one of their daughters, married Johan de Mepsche around 1561, a notorious Groningen heretic hunter and a staunch Catholic supporter of the Spanish monarchy during the Dutch Revolt. Their daughter, Mary de Mepsche, married Johan Kyff van Frens and inherited this treasured book. The manuscript then passed down to her sister’s son Egbert Clant and his wife Beatrix, and eventually to their daughter, Maria Catrina Clant. An additional note in the book traces its journey through the hands of women in the family:

This book is left as inheritance to Lady Agnes van Münster’s daughter Mary de Mepsche, and further to Egbert Clant and Beatrix van Ewssum who gave the same to their daughter Mary Catherine Clant, 4 April 1639.

MS 371 is the first book of hours at New College that we can definitively say was owned by women, though likely not the only one. Other additions by its owners, including the Ten Commandments in the vernacular, and notes on ‘watery’ zodiac signs, along with the worn initials on prayers and an image of Christ, reflect the deep personal devotion of this family over at least four generations. Their religious dedication is also evident from their sizeable donations to several monasteries, including Marienstatt, Keppel, and Ter Apel, where the coat of arms of Agnes van Münster and Johan de Mepsche can be found in a stained glass window.

AND MORE: MS 323 AND MS 310

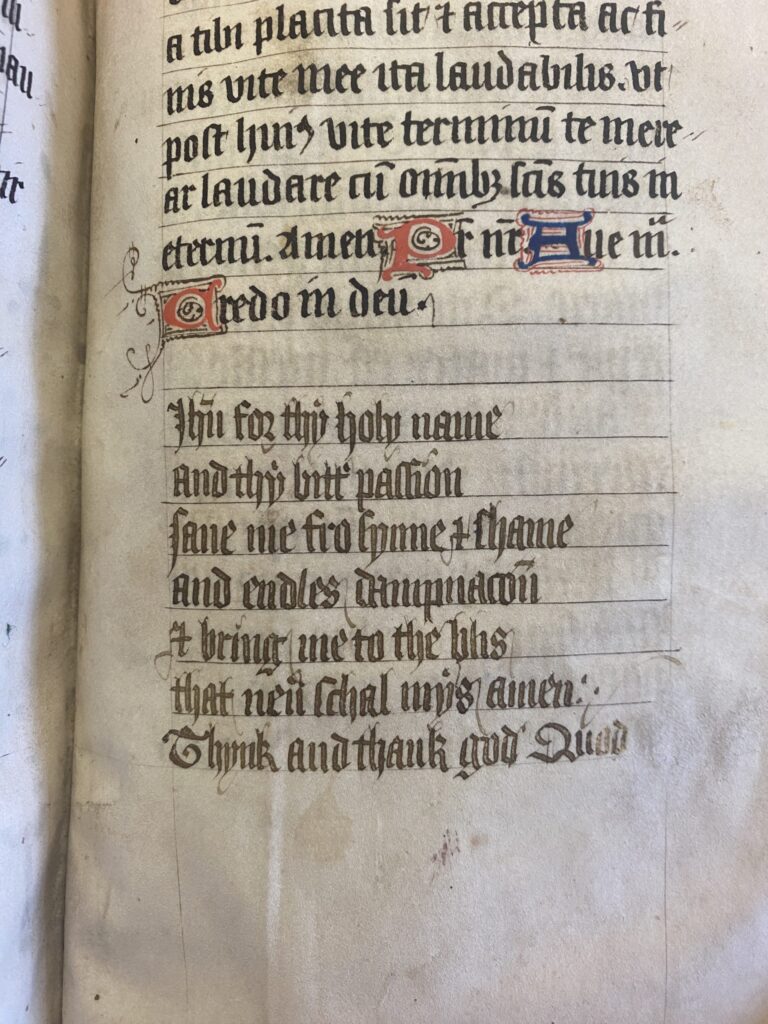

Although MSS 369 and 371 have been the focus of my study, there are marks of use and ownership in each of New College’s books of hours. MS 323, a 16th-century Flemish manuscript, contains a Spanish inscription beginning ‘Estas horas van Lohesi(?)’ and further inscriptions in English detailing the births of two children, Jane and William Watson, in 1614 and 1615. MS 310, an early 15th-century book of hours, features a Middle English religious lyric and a signature possibly belonging to a ‘Henry Knyght’.

There is still much to uncover about these manuscripts and their owners, especially the MSS I have mentioned only briefly. If anyone is interested in viewing these manuscripts themselves, please contact New College Library or the Head Librarian (Christopher Skelton-Foord) to arrange an appointment.

If you’d like to read more, my full article on these manuscripts has recently been published online, open access, in New College Notes 21 (2024).

My heartfelt thank you goes out to Marlene Schilling and Kat Smith from MWW, the New College Library team, and TORCH for making this event happen. I’m again deeply grateful to Prof. Henrike Lähnemann and Dr Friedel Roolfs for their incredible work on the transcription and translation of MS 371, and to Rakoen Maertens and New College Archivist Michael Stansfield for their assistance with the MS 323 inscriptions.

Bibliography:

Deschamps, J. and Mulder, H. (1998–2009). Inventaris van de Middelnederlandse handschriften van de Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België (voorlopige uitgave). Brussels: Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België.

Reinburg, V. (2009). ‘For the Use of Women’: Women and Books of Hours. Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4, pp. 235–240.

Rudy, K.M. (2016). Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

van Weringh, J.J. (1981). De Selbachs. Gruoninga: Tijdschrift voor genealogie en wapenkunde, 25e–26e, pp. 1–30.