Report by Leonie Erbenich, Visiting Graduate Student in Modern Languages, on a workshop with Giles Bergel for the History of the Book students in Modern Languages 2025. Cf. the History of the Book blog on the workshops in 2024 ‘Seeing Materiality through a Computer’s Eyes‘ and 2023 ‘Digital Tools for Image Matching‘

How Archivists can benefit from Computer Vision

Dusty reading rooms are hardly the place where you’d expect to find cutting-edge technology — but AI researchers and libraries have formed an unlikely symbiosis in the field of Computer Vision, a technology that transforms images into geometrical data. You’ve probably come across this branch of AI in your daily life – e. g. when parking your car with park assist, or identifying a plant via an app, or trying to track down a pair of shoes with google lens. But Computer Vision is also a real gamechanger when it comes to unveiling the History of Books.

Humans mostly open books because they want to read the text that’s inside. The absence of this intent in the computational gaze allows for a different focus: Each page becomes first and foremost an image, a surface consisting of shapes and lines that can be measured and compared.

Even before the digital age, bibliographers were already looking for ways to see differences between seemingly identical pages: The McLeod Portable Collator for example is a wonderfully eccentric, mechanical device that overlaid two printed pages optically. (More information on library machines can be found on the Bodleian blog)

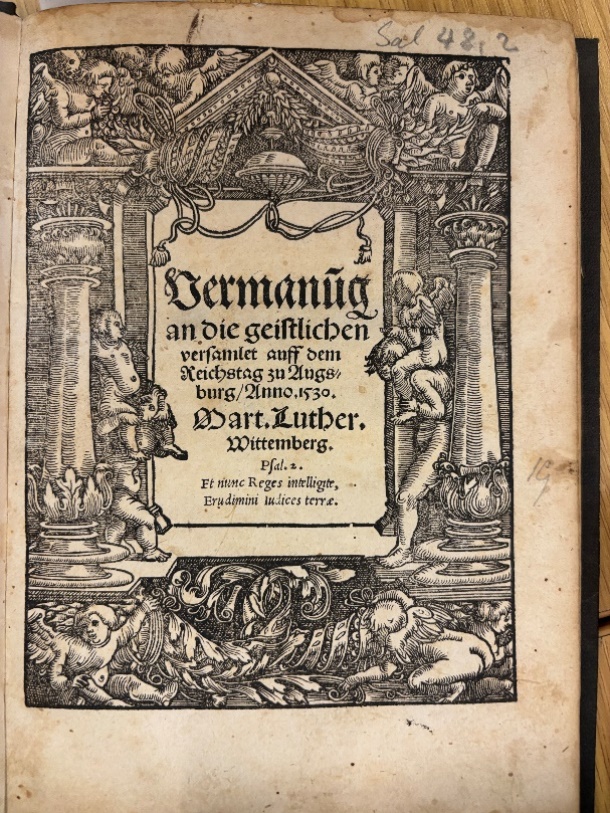

Today, those ingenious optical tools have digital descendants: Software such as ImageCompare, developed by Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group, can compare scans of bookpages and automatically highlight even the tiniest shifts in type, punctuation, or ink. What once required hours of eye-straining concentration can now be done in seconds. Funfact: The beloved “before- after” slide feature on Instagram is only one of several options ImageCompare offers to make it easier to “spot the difference”- for example in these title pages of reformation pamphlets from 1530:

Nevertheless, these tools are not magical “brains in a box” that spit out research results, as Dr Giles Bergel, Digital Humanities Researcher in the Visual Geometry Group Oxford, puts it. They just act as magnifiers that help spotting similarities and differences in material. It’s up to humans to interpret the data: Woodcuts, for example, were often reused across countless editions of books or manuscripts at different times and places. Paradoxically, the newer looking print can sometimes be the older one. Scotland Chapbooks (https://data.nls.uk/data/digitised-collections/chapbooks-printed-in-scotland/) is capable of searching a large dataset for illustrations and visually group them together, allowing researchers to trace how a single woodcut might have changed over time — a crack deepening, a border wearing thin, holes left by a bookworm.

Research Examples

Giovanna Truong, a former History of the Book student, used ImageCompare to identify identical illustrations in two different Yiddish Haggadot-uncovering a link between the two printers of the books based in Venice and Prague.

Blair Hedges, evolutionary biologist at Pennsylvania State University, studied the different patterns of wormholes which appear as white dots on prints and was able to attribute them to two different species of beetles. The holes in the woodcuts revealed how they were spread in Europe at the time, coincidentally strikingly in accordance to the distribution of Catholics and Protestants in Europe…

These examples show how the use of AI reveals formerly invisible patterns that can serve as clues to a book’s life and travels. And it might help to shift the image of dusty librarians and archivist trailing behind their time – as it is actually quite the reverse.